SRI RAMANASRAMAM

VOL. 18, NO. 3

Dear Devotees,

In this March issue we continue with the life story of T.K. Sundaresa Iyer and the many riveting reminiscences he shared recalling his forty years with Bhagavan.

Also this issue, we look at mental chatter which modern research has correlated with cardio-vascular disease, anxiety and depression. Bhagavan cautioned us about unwanted thoughts in the mind and in this segment, we look for ways to address the mind’s background noise.

For videos, photos and other news of events, go to https://sriramanamaharshi.org or write to us at saranagati@gururamana.org. For the web version: http://sriramana.org/saranagati/March_2024/ or https://saranagati.arunachala.org/issues/

In Sri Bhagavan,

Saranagati

Table of Content

Calendar of Ashram Events

8th Mar (Fri) Mahasivaratri/Pradosham |

14th Apr (Sun) Tamil New Year/Nirvana Room Day |

15th Mar (Fri) Sri Vidya Havan |

17th Apr (Wed) Rama Navami |

22nd Mar (Fri) Pradosham |

21st Apr (Sun) Pradosham |

24th Mar (Sun) Pournami |

6th May (Mon) Sri Bhagavan’s 74th Aradhana |

6th Apr (Sat) Pradosham |

31st May (Fri) Maha Puja |

9th Apr (Tue) Telugu New Year |

18th Jun (Tue) Cow Lakshmi Annual Puja |

IN PROFILE

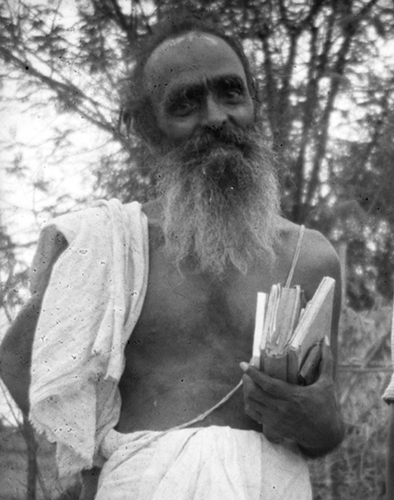

T.K. Sundaresa Iyer (pt. II)

In the previous issue, we saw how Bhagavan and devotees moved down from Skandasramam to establish an Ashram community at the base of the Hill. The move entailed transforming the rough terrain into a liveable area. Dandapani Swami and other devotees worked tirelessly to clear the cactus and briar, levelling the ground. A simple woman who in earlier years had brought food to Bhagavan on the Hill together with her husband, but now widowed and living by selling dosai, came to Bhagavan in the first months after his moving down from the Hill. When she saw her Swami living beneath the open sky, she exclaimed, “Aye! Swami is sitting on the ground, exposed to the sun!” From that moment, she insisted on having a concrete platform constructed and covering it with palm leaves. Apart from Mother’s Samadhi, this was the first structure at the new Ashram. But other structures would follow in turn. Two thousand rupees were raised and spent on thatched sheds to serve as kitchen, storeroom, dining hall and living quarters, and ashramites along with Bhagavan did most of the work.

In 1924 two huts, one opposite Mother’s samadhi and the other to the north of it, were erected. The first year after leaving Skandasramam was pivotal and Bhagavan’s accessibility and the increased contact with the outside world proved providential, opening the door for newcomers like Kapali Sastri, Griddalur Sambasiva Rao and Viswanatha Swami, all who came in 1923. Within a few years, funds were raised for what was to be a bricked kitchen and dining hall. However, in a remarkable turn of events, the space was at the last moment transformed into a darshan hall for Bhagavan. Meanwhile, Kavyakanta and his pupils remained up on the Hill. This meant that TKS had to divide his time between Vedic classes at Mango Tree Cave and darshan below with Bhagavan in the newly built darshan hall. The Muni and his students frequently came down to sit at the feet of Bhagavan. Such sessions were more than mere gatherings but invariably involved profound exchanges of spiritual power and wisdom:

When the Muni was in the Hall, Sri Maharshi could be seen in the full bloom of his being. The discussions ranged over various schools of thought and philosophy, and it was a period of great literary activity at the Ashram. Kavyakanta, Kapali Sastry, Muruganar, Lakshmana Sarma, Arunachala Sastriar of the Madras Gita fame, Munagala Venkataramiah, author of Talks with Sri Maharshi, Sivaprakasam Pillai, and a host of others, used to be in the Hall, which was open all through the hours of day and night. It was then the world of freedom of Sri Ramana, our Lord, Guru and very Self. Our lives were based and turned upon that one central personality. Nothing gave us greater joy than to be in his presence as often as possible and to do his bidding. 1

Though settled in the new Ashram, funding was not sufficient for constructing more brick dwellings, so Bhagavan and the sadhus contented themselves with a simple rustic life. They lived in grass huts, which proved enough for the simple vocation they had chosen for themselves. They had only one luxury, a luxury that few in the world enjoyed and the only one they required, namely, Bhagavan in their midst.

Bhagavan’s Compositions

Over the years since the days at Virupaksha, Bhagavan had composed various poetic works and translated others. Devotees proposed that they be collected and published, a proposal Bhagavan accepted. The proofing work had been done but there was need of a preface and no one coming forth to write it. TKS narrates:

It was about 1927 when Sri Bhagavan’s Nool Thirattu in Tamil was under preparation to be published. There was talk among the Ashram pundits that the book must have a preface although the devotees of Maharshi considered that nobody was qualified to write the preface. The pundits proposed the writing of a preface, but none of them came forward to write it, each excusing himself that he was not qualified for the task. It was a drama of several hours as one proposed another for the purpose, and each declined the honour. Bhagavan was watching all this quietly. At about 10.30 in the night, as I was passing beside the Hall, Sri Bhagavan looked at me and said, “Why not you write the preface yourself?” I was taken aback at his proposal, but meekly said, “I would venture to write it only if I had Bhagavan’s blessing.” Bhagavan said, “Do write it, and it will come out all right.” So, I began writing in the dead of night, and to my great surprise within three quarters of an hour I made a draft as if impelled, driven by some supreme force. I altered not even a comma of it, and at 2 am in the early morning I placed it at his feet. He was happy to see how the contents were arranged and to note the simplicity of the expressions used. He passed it as all right and asked me to take it away. But as I had taken the written sheets of paper only a few steps, Sri Maharshi beckoned me to show them to him once again. I had concluded the Preface in the following way: “It is hoped that this work in the form of Bhagavan’s grace will give to all who aspire to eternal truth, the liberation in the form of gaining supreme bliss shaped as the taking away of all sorrow.” Maharshi said, “Why have you said, ‘It is hoped’? Why not say ‘It is certain’?” So saying, he corrected with his own hands my ‘nambukiren’ into ‘tinnam’. Thus, Sri Maharshi set his seal of approval on the book, giving to his devotees that great charter of liberation, in the form of his upadesa which leaves no trace of doubt about it in the mind. 2

In 1929, Sri Kavyakanta left Tiruvannamalai and placed TKS in Bhagavan’s care. In the very first letter he wrote to Bhagavan, he asked Bhagavan to take special care of TKS:

I was at school when that letter was received, and the Maharshi tucked it under his cushion. He pulled it out, read it to me when I returned from school, and said: “Look here, you must not run away. I am answerable to Nayana; he may come at any time and claim you from me.”

TKS continues his narration:

Our happiness in the presence of Sri Bhagavan was comparable to the joy of the hosts of Siva on Mount Kailasa. Sri Bhagavan used to say, “Kailasa is the abode of Siva; Arunachala is Siva Himself. Even in Kailasa things are as they are with us here. Devotees go to Siva, worship him, serve him, and hear from him the interpretation of the Vedas and Vedanta day in and day out.” So it was Kailasa at the foot of the Arunachala Hill, and Arunachala Paramatma in human form was Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi. 3

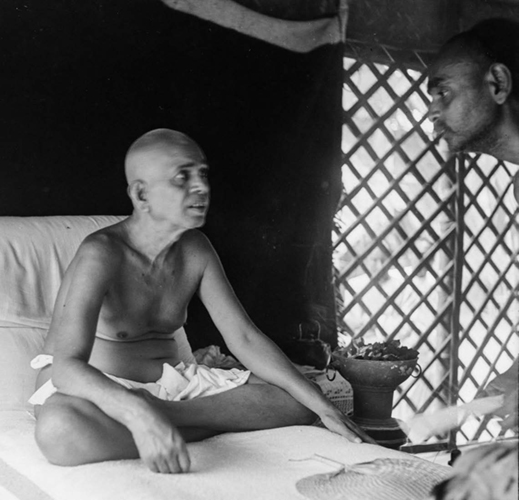

Deepavali Darsan

Up until this time, TKS had been occupied with study of the Vedas under Nayana, visiting Bhagavan regularly, raising a family and teaching in the local school, all of which had to be balanced within the 24 hours of the day. Very often TKS would miss a night’s sleep to maintain his schedule replete with the richness of a daily life under Bhagvan’s divine guidance. Sleep or no sleep, TKS made use of every opportunity to be in the Master’s presence:

Bhagavan in his embodied state occupied our whole heart, being dear to us as father, mother, God, and Guru, all in one. We were loath to leave his presence, be it night or day. We slept outside the Old Hall, and Bhagavan was always visible to us on the sofa from where we were. On the night prior to Deepavali in 1929, the first year of my settling in the Ashram, Bhagavan suggested my going home for Gangasnanam (‘bath in the Ganges’). To me the very sight of Bhagavan is a bath in the Ganga, the sight of Bhagavan is the worship of Siva, the sight of Bhagavan is the fulfilment of every ritual and the practice of all austerities. Yet I did not want to go against the mandate of Bhagavan so I went home late in the night. I was impatient to be back with Bhagavan, so I woke my wife and children up even at 2 am, finished the ceremonial Ganges bath, and hastened to his blessed Presence. Bhagavan lay reclining on the sofa. It was about 2.30 am; I made the usual prostration and sat down by the sofa. All of a sudden, an aura was visible around Bhagavan’s head. It was like the glory with clusters of evenly arranged flames, just as we see round the deities in our temple processions. Bhagavan’s face shone with a beaming smile. It appeared to me that Bhagavan was giving darshan of Sri Nataraja, the Lord of the Cosmic Dance. In my ecstasy, I think I must have sung hymns from Thevaram, which I love as dearly as the Vedas. The vision lasted for half an hour, and then the glory vanished. At 4 am Bhagavan sat up for his Pansupari. I related to him what I had seen, and again he just gave a beaming smile. 4

Around this period, TKS asked Bhagavan to give him clear instructions as to what direction he should proceed in the spiritual life. Bhagavan gave him Kaivalya Navaneeta to read and explained to him its inner meaning:

From that time on I gave myself completely to spiritual life. I did my duty at school and supported my family, just as something that had to be done, but it was of no importance to me. It was wonderful how I could keep so detached for so many years; it was all Bhagavan’s Grace. One Amavasya (new moon day) all the Ashram inmates were sitting down for breakfast in the dining room. I was standing and looking on. Bhagavan asked me to sit down for breakfast. I said that I had to perform my late father’s ceremony on that day and would eat nothing (Usually the ceremonies are done to enable the ancestors to go to heaven). Bhagavan retorted that my father was already in heaven and there was nothing more to be done for him. My taking breakfast would not hurt him in any way. I still hesitated, accustomed as I was to age-old tradition. Bhagavan got up, made me sit down and eat some rice cakes. From that day on, I gave up performing ceremonies for ancestors. 5

On one occasion when Chinnaswami got angry with TKS, the latter was so rattled by the interaction that he could not eat his dinner. The next morning, though hungry, he was still shaken by the events the night before and therefore invented a pretext for leaving the Ashram without eating, saying that he was in a hurry to get to town to meet his pupils who were waiting for him. TKS recorded the following interaction:

“The cat is out of the bag,” said Bhagavan. “Today is Sunday and there is no teaching work for you. Come, I have prepared a special sambar for breakfast, and I shall make you taste it. Take your seat.” So saying, he brought a leaf, spread it before me, heaped it with iddilies and sambar and, sitting by my side, started cutting jokes and telling funny stories to make me forget my woes. How great was Bhagavan’s compassion. 6

Mrs. TKS’s Cooking

TKS’s wife used to prepare food for Bhagavan each afternoon and bring it to the Ashram. Bhagavan often asked her to give up this custom but Mrs. TKS could not. One day Bhagavan put his foot down: “This is the last time I am eating your food. Next time I shall not.” TKS describes what happened next:

As it turned out, the same day Bhagavan was giving instructions in the hall as to how a certain dish should be prepared. The next day my wife brought it all ready. Bhagavan remembered what he had told her, but what could he do against her imploring look? He tasted her food and said that it had been prepared very well. Such was his gracious courtesy to his devotees. 7

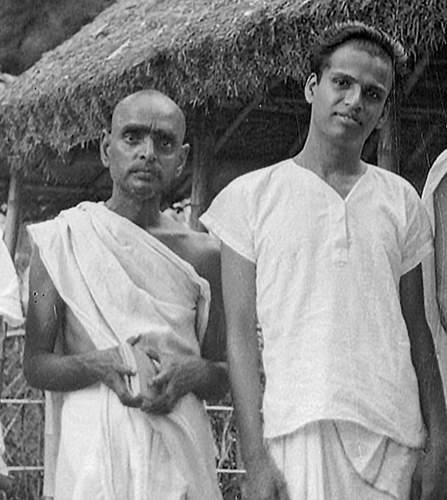

The Lazy Son

All TKS’s family naturally became enthralled with Bhagavan as the life of the Sundaresa household revolved around the Sage. Once when TKS’s second son was preparing for exams, the boy and his father worried about the outcome since the youngster had never been keen to study and therefore tended not to do well in school:

The time for his final high school examinations was rapidly approaching and the boy’s sole preparation was the purchase of a new fountain pen. He brought it to Bhagavan and asked him to bless the pen with his touch so that it would write the examination papers well. Bhagavan knew his lazy ways and said that having hardly studied, he could not expect to pass. My son replied that Bhagavan’s blessings were more effective than studies. Bhagavan laughed, wrote a few words with the new pen and gave it back to him. And the boy did pass, which was a miracle indeed. 8

Letter Writing

In those days TKS was attending to the Ashram’s foreign correspondence. His English was perfect, (as was his Tamil and Sanskrit) and thus, he was well-suited to this work. He would thus draft replies to letters received by the Ashram and show them to Bhagavan, get his approval, and put in the final touches before despatching them:

We used to receive some very intelligent and intricate questions. These questions and the answers would have formed a very enlightening volume.

Going Away?

At one point, it appeared that TKS would have to do the unthinkable and shift to another town for a job offer. He narrates:

Once I got a job offer in another town which carried a good pay. I intimated my consent and received an appointment order by wire. I showed the wire to Bhagavan. “All right, go,” he said. Even before I left the hall, I felt gloom settling over me and I started shivering and complained in my grief: “Forty years I have been with Bhagavan and now I am going away. What shall I do away from Bhagavan?” “How long have you been with Bhagavan?” Bhagavan asked. “Forty years.” Then, turning to the devotees, Bhagavan said, “Here is someone who has been listening to my teaching for forty years and now says he is going somewhere away from Bhagavan!” Nevertheless, the job fell through. Once I wrote two verses in Tamil, one in praise of the Lord without attributes, the other of the Lord with numberless forms. In the latter I wrote: “From whom grace is flowing over the sentient and insentient.” Bhagavan asked me to change one letter and this altered the meaning to: “who directs his grace to the sentient and the insentient.” The idea was that grace was not a mere influence but could be directed with a purpose where it was needed most. Bhagavan gave us a tangible demonstration of God’s omnipotence, omniscience and omnipresence. Our sense of ‘I’ would burn up in wonder and adoration on seeing his unconditional love for all beings. Though outwardly we seemed to remain very much the same person, inwardly he was working on us and destroying the deep roots of separateness and self-concern. A day always comes when the tree of ‘I’, severed from its roots, crashes suddenly and is no more, this is the Guru’s Grace! 9

(to be continued)RAMANA REFLECTIONS

Managing Internal Chatter

MANY who come to the Ramana path find Bhagavan’s teachings difficult to practice. Self-inquiry they say can easily degenerate into mechanical questioning and Bhagavan’s surrender can become a futile effort at letting go. In either case, the mind clings tenaciously, refuses to settle down, and is beset with an endless stream of thoughts. We may proclaim our willingness to give up everything for Bhagavan, but the mind intervenes and upsets even the sincerest resolve. With its constant pounding and weaving, repetitive thought-streams, interminable aimless ruminations, and steady reverberations of dead words, its busy-ness won’t leave us alone. To make matters worse, when the mind is busy with thoughts, they are often beset by worries, anxieties, or fears, all of which combine to complicate a life already overbooked with the daily demands of the modern era. Meditation and self-enquiry are just two more things to add to an already overwhelming daily to-do list.

The relentless trolling of the mind, like living in a house with all the water faucets fully open, is one of modern humanity’s most debilitating conditions. Medical science tells us that one gram of brain matter burns as many calories as 22 grams of muscle at rest, hence diversion through continuous rumination is expensive indeed and depletes the mind and body, draining it of the vitality necessary for living a full and meaningful life. Bhagavan comments:

The mind is only a bundle of thoughts. The thoughts arise because there is the thinker. The thinker is the ego. The ego, if sought, will vanish automatically. The ego and the mind are the same. The ego is the root-thought from which all other thoughts arise. 10

An ill-regulated mind is its own punishment, said the fourth-century saint, Augustine. But what is an irregulated mind? It is a mind that is compulsive in its activity and does not seem to know where it is going or why. If constant flitting and shallow processing hinders meaningful engagement with the world internally and externally, they are born of a continuous stream of thoughts that run through the mind in an unceasing internal dialogue. In more extreme moments the mind races down the highways of our life at high speed unable to slow down for fear of not racing ahead.

In the fast-paced modern world filled with multitasking, information overload, image saturation, and device-driven overstimulation, maintaining sustained attention on anything for long is made challenging. But what if all this trouble were not dependent on external conditions? What if all the noise of the mind were not coming from the world, but were coming from within? What if the means of managing the world’s encroachment in our lives starts with us?

If we see ourselves as ones afraid in a world we never made11, as the line goes, we may imagine it to be the world’s fault. But Bhagavan reminds us that misery is only unwanted thought 12. If you clean up the mess within, the world shines. On the other hand, Bhagavan says, if you go the way of your thoughts, you will be carried away by them and you will find yourself in an endless maze. 13

Increasing complexity in the modern era has put pressure on family life, and the early life nurturing requisite for sound development and growth of a child has deteriorated in recent decades. Demands made on mothers in the late 20th and early 21st century make care giving and the deep nurturance of young children less assured. The serenity of a mother amid the turmoil of her infant’s loud cries permits her to simply stop what she is doing and to spend the needed time with the child. But in a stress-laden modern world, serenity is in short supply and mothers are less enabled to perform this most essential mothering task simply on account of the demands made on their time. Decline in the quality of care at home in early life is widespread but is just one of many symptoms of general social and cultural decline in the 21st century.

An irregulated mind and its obsessive chatter is indicative of a psyche and heart in crisis, even if such conditions have become normalized. Children who grow up in hectic environments may develop a persistent internal dialogue that causes them to question their self-worth and capabilities. Their proclivity to mental chatter may be born of neglect experienced in childhood and a lack of quality care from the parents, giving rise to self-talk and self-evaluation that are dismissive and indifferent. Early life maternal neglect can alter the brain’s stress response systems, making an individual more susceptible to anxiety and stress. Heightened stress sensitivity can manifest as mental chatter where the mind is perpetually engaged in managing fears and anxieties revolving around themes of insecurity, threat, or self-doubt, residues of the early life trauma of maternal neglect. 14 But then, what is mental chatter?

Mental chatter is a proliferative chain of reactivity. Reactivity in the mind is self-propelling and mostly unconscious. It is moreover sensitive to any effort to compel it to stop. Such an effort could be seen as one more reactive moment in the chain, ironically reinforcing the proliferation. Our job is to make use of Bhagavan’s inquiry to investigate the chain as a whole, as well as investigating discrete episodes within it, namely thoughts and images. In this way, we can slow it down. Investigate and the thoughts will cease,15 Bhagavan says.

We make our inquiry pinpointed to see if we can discover more essential, fundamental causes for discrete elements in the chain, examining very patiently its component parts. When the pace of successive thoughts triggered by the previous thought goes too fast, we pan back and observe the chain as a whole: who or what is driving this? Sometimes it is already enough just to observe that we are caught up in a chain of reactivity. If we can gently slow the pace of mentation, remembering to make a note that the chain is not myself—not the Self—we find we are enabled to disentangle some of the nexuses of accumulated thoughts and samskaras that are at the root of the cycle. If, as has been said, analysis is paralysis, we avoid speculating in an analytical way but merely observe the unfolding sequence and inquire into its sources. We look for what Bhagavan speaks of as the root of the mischief:

If a man considers he is born he cannot avoid the fear of death. Let him find out if he has been born or if the Self has any birth. He will discover that the Self always exists, that the body which is born resolves itself into thought and that the emergence of thought is the root of all mischief. Find wherefrom thoughts emerge. Then you will abide in the ever-present inmost Self and be free from the idea of birth or the fear of death. 16

Spiritual Instructions: Chapter 2, §10

Thoughts in the Mind

Why do thoughts of objects arise in the mind even when there is no contact with external objects?

All such thoughts are due to latent tendencies (purva samskaras). They appear only to the individual consciousness

(jiva) which has forgotten its real nature and become externalised. Whenever particular things are perceived,

the enquiry “Who is the one that sees them”? should be made; they will then disappear at once. —

Resilience

Pacifying the mind through the consolidation of attention is what we are talking about here. This has not only been a religious goal of the highest order down through the ages but, in our modern hyperdigitalised world, is an urgent public health need. Just consider findings from the US National Institute of Mental Health: about eighteen percent or forty million adults in the United States suffer anxiety disorders. Additionally, thirty million or one in ten are daily taking pharmaceutical anti-depressants. These trends are not so marked in India. But around the world a rise in the frequency of anxiety and suicides are being reported. If affective disorders as well as ordinary stress are attributable in part to psychic loose ends, it only stands to reason that when we tidy up the mind, things run much smoother, and former stressors are less stressful.

In neuropsychology this smoothness is called ‘resilience’. Resilience is a measure of the rate a subject returns to baseline in the aftermath of a stressful event. Research shows that cortisol levels in meditators return to normal much faster in the wake of a stressful event than in non-meditators. Stress is a negative measure of how we deal with stressful events. In the laboratory setting, skin irritation brought about by the external application of chili powder has been documented to normalize faster in those experienced in meditation. While researchers can measure with some accuracy the capacity to tolerate traumatic events and return to baseline, they cannot scientifically pinpoint the cause of increased resilience in meditators. However, without being able to prove it, anyone experienced in meditation and inquiry can answer this question readily: our resilience is increased by deep engagement with meditation silence and awareness. That is because meditation awareness, not to mention Bhagavan’s inquiry foster the natural processing and assimilation of unconscious, undigested, emotional and psychological material. Compassion studies show that meditation elevates empathic and altruistic sensibilities in just six weeks of meditation training.

What the traditions teach us is that often there is no need to do much with unwanted emotional or psychological material apart from noticing it, naming it, and being present to it. When we practise this, we discover that vexations no longer trouble us. Rather, it is that which remains hidden from view that cripple us. Therefore, meditation is in part the practice of excavation, continually uncovering what lies hidden beneath the threshold of consciousness and bringing it into the light of awareness. Sin confessed is sin no more, goes a saying. What is seen and acknowledged becomes innocuous. Bhagavan adds:

All thoughts are from the unreal ‘I’. i.e., the ‘I’- thought. Remain without thinking. So long as there is thought there will be fear…. So long as there is thought there will be forgetfulness. There is the thought “I am Brahman”; forgetfulness supervenes; then the ‘I-thought’ arises and simultaneously the fear of death also. Forgetfulness and thought are for ‘I-thought’ only. 17

Training Attention

Meditation is nothing more than letting one’s attention rest on whatever arises without necessarily intervening. Just noticing and identifying non-judgmentally whatever appears is sufficient to initiate its healing. From the meditation point of view, trying to actively heal wounds may slow down the process. If we try to manipulate ego, it grows stronger; the opposite extreme is its total neglect allowing it to continue unchecked. Rather, observing and naming our pride or selfish motivations at their place of origin is enough to initiate their maturing.

We think we know ourselves and often identify with the chatter of our minds, calling it Self. But mental chatter is transient like the passing clouds. Who we really are can only be discovered below the threshold of the thinking mind. Bhagavan comments:

Shadows on the water are found to be [undulating]. Can anyone stop the [undulating] of shadows? If they should cease to undulate you would not notice the water but only the light. Similarly, to take no notice of the ego and its activities but see only the light behind it. The ego is the I-thought. The true ‘I’ is the Self. 18

The ego is not intrinsic but is derivative of the body, memory, samskaras, perception, and the will to live, etc. Ego is a paint-by-number self-portrait colored by mental chatter. Internal chatter issues from the ego’s reflex to the fear of mortality and the relentless drive for self-preservation. Magical thinking about the everlasting nature of body and personality is a defense mechanism that seeks to insulate us against the reality of eventual bodily death.

But ego is not equal to the Self, Bhagavan insists. The ego is comforting because it is our property. But it is unreal. The Self by contrast cannot be owned or possessed but is the everlasting ground. The mental chatter that supports the ego illusion must be gotten rid of before the Self can be seen and known, Bhagavan tells us.

Training the capacity to move below the threshold of thought is simply the most urgent and important step one could take in one’s spiritual life. Meditation traditions have this as a central part of their training, often using simple meditation tasks as a means of consolidating scattered attention and focusing it in a single direction. When we talk of training attention as a treatment for chronic anxiety, it is misleading. From the neurological point of view, anxiety is nothing other than a disorder of attention, namely, the constant flitting of attention from one thing to the next, wherein disparate thoughts appear in never-ending succession one after the other. Bhagavan says:

In the Bhagavad Gita it is said that it is the nature of the mind to wander. One must bring one’s thoughts to bear on God. By long practice, the mind is controlled and made steady. The wavering of the mind is a weakness arising from the dissipation of its energy in the shape of thoughts. When one makes the mind stick to one thought, the energy is conserved, and the mind becomes stronger… The satvic mind is free from thoughts whereas the rajasic mind is full of them…[The strength of the mind is its] ability to concentrate on one thought without being distracted. 19

The Upanishadic teaching of neti, neti, much like Bhagavan’s vichara, urges us beyond the surface level of the mind, cluttered as it is with labels, shapes, endless thoughts and other such transient phenomena. In the Gita, Krishna resolves Arjuna’s dilemma by teaching him mastery of the mind, detachment from desires, and disciplined action, helping Arjuna to overcome mental chatter so that he might act with clarity, free of attachment. As for Bhagavan, when Seshadri Swami, known for his formidable abilities at mind-reading, sat before Bhagavan to discern what was going on in the youngster’s mind, he discovered “there was no one there.”

It has been said that failure in the religious life is not due to our prayers being denied. Our failure is in not knowing what to pray for, not knowing how to direct our efforts in sadhana, and not knowing what to aim for in the pursuit of purity of heart, out of touch as we are with ourselves. Our will is largely governed by impulse and the chatter of the mind.

Studies in neurology cannot illumine the requisite subtle transitions at the heart of faith. We long for courage to face the disappointments that come with daily living so that we might deepen our faith and participate more meaningfully in our earthly walk. If our sight had been dimmed, this veiling effect of the mind’s chatter diminishes with time through inquiry. If our dynamism had formerly been stifled and flattened by constant preoccupation with diversion through thought and involuntary mental chatter, the ship begins to right itself as soon as we learn how to quieten the mind. Lao Tzu reminds us:

To the mind that is still, the whole universe surrenders. 20

The Waters of a Deep Well

Papering over life’s discontents, disappointments, and sufferings through diversion in extraneous rumination is like ignoring a septic wound in the flesh: by not tending the wound, we avoid experiencing the discomfort that comes with cleaning and disinfecting it. But such avoidance comes at a price. As we delay, the infection spreads and the pain momentarily deferred returns with ever-increasing vigour. The Heart is no different. If we make use of inquiry to treat the injured parts of the Heart, though uncomfortable at first, a lightness soon begins to pervade our being and a Heart formerly burdened with the heaviness of unhealed wounds springs to life, and we recall what Rumi once said about the wound being the place where the Light enters in.

Inquiry is the art of engaging the unhealed parts of the psyche through awareness. This is true healing and true spiritual growth. By refining and smelting the dross in the forge-fires of interior investigation, we are made clean and whole and find we are not so easily thrown off balance when life deals us a hard blow. An ancient proverb reads, strong winds are powerless to disturb the waters of a deep well.

Inquiry has the effect of breaking up spiritual stagnation and breathing life into the dead circularity caused by habitual thinking. Meditation inquiry is the direct route to inner housecleaning and binds up the loose-ends of the Heart. Old grief-wounds long rejected by the conscious mind come to the fore, teaching us how to absorb them and transform them by simple acknowledgement. The intimacy of meditation begins by giving needed attention to the split-off fragments lurking in the caverns of the Heart. The process, while not always easy, leads to a more profound joy leavened by the earlier sorrow.

A verse from 11th-century China says, “If intense cold strikes not to the bone, how can plum blossoms be fragrant?” 21 The revered plum tree, it should be mentioned, only blooms in the bitter winter cold. Likewise, our true healing only comes through an intentional encounter with the delicate sorrows that are bone-marrow deep. —

(to be continued)In Focus: Special Edition

For the newly released, In Focus: Special Edition, see: https://youtube.com/embed/IKxXh7T16Mg. For the February edition, see the following: https://youtu.be/amaVtPcJBUA?si=kGaKPIxSzxhsVXXX. —

Events at Sri Ramanasramam: Sundaram Iyer Day

Following Bhagavan’s morning puja on 21st February, devotees gathered in the Mother’s Shrine to observe Bhagavan’s father’s Aradhana Day. Devotees chanted a verse from Bhagavan’s Navamanimalai, ‘I was born in holy Tiruchuzhi, the seat of Bhoominatheswara, renowned throughout the world, to the virtuous Sundara and his faithful wife Sundari’, (v.8). —

Obituary: Smt. Kalyani Kapali

Smt. Kalyani Kapali attained Sri Bhagavan’s lotus feet on 3rd November 2023. She was 92. She grew up in Ramana Nagar and was well known in the ashram circles between 1931 and 1950. Her father, Sub-Registrar R Narayana Iyer came to Bhagavan from Chetpet with the intention to scoff as he was a skeptic of religion and all things religious, including sannyasins and sadhus. But when he found himself before Bhagavan, he noticed that “a solemn stillness pervaded the air and there was absolute silence.” In the early 1930s the Sub-Registrar was posted to Tiruvannamalai and came with his wife and children, all of whom were blessed to be in the company of Sri Bhagavan on a daily basis.  Kalyani began to be referred to as ‘The Ashram’s Daughter’ by then President, T.N. Venkataraman (Venkatoo Mama). Kalyani would often sing the song Saranagati, a song of absolute surrender to the divine, in the presence of Bhagavan. Her grief on Bhagavan’s Mahasamadhi day was visible in the Government News reel (pictured right). Often seen around the ashram where she spent most of her childhood and adolescent years, she could be seen treading on the mountain and every corner of the ashram and enjoyed Bhagavan’s abundant grace. She breathed her last while in meditation and prayer to Bhagavan. —

Kalyani began to be referred to as ‘The Ashram’s Daughter’ by then President, T.N. Venkataraman (Venkatoo Mama). Kalyani would often sing the song Saranagati, a song of absolute surrender to the divine, in the presence of Bhagavan. Her grief on Bhagavan’s Mahasamadhi day was visible in the Government News reel (pictured right). Often seen around the ashram where she spent most of her childhood and adolescent years, she could be seen treading on the mountain and every corner of the ashram and enjoyed Bhagavan’s abundant grace. She breathed her last while in meditation and prayer to Bhagavan. —

Obituary: Smt. Karamsetty Satyavathi

Born in 1958 at Tenali, Smt. Karamsetty Satyavathi married Sri Karamsetty Guru Prasada Rao and raised three children. In 1986, the couple established a Ramana Kendra at their home in Manganapudi Beach, southeast from Vijayawada where her husband had a business. They regularly performed Laksha Bilva archana and invited Bhagavan’s devotees to lecture at the weekly meetings held each Sunday. They also conducted meetings in the college grounds where her husband distributed Bhagavan’s books. All prasadas were made by Satyavathi. “Bhagavan Nilayam Dayagala Hrudayam” was the name given for the hall in the family home dedicated to these weekly meetings.

Satyavathi lost her husband in July 1994 but continued to spread the word about Sri Ramana. When she went to live with her son in Ananthapur, she delivered speeches about Bhagavan on the Anantapur District Radio Station which were broadcast all over the district. In 2007, she took a room near Sri Ramanasramam and assisted devotees who came for Giri Valam, allowing them to place their luggage in her small room. She felt blessed to prepare the vibhuti and kumkum packets distributed to devotees during the Ashram pujas. When Satyavathi fell ill In July 2023, she did not worry about declining health, saying it was all his will. On 13th January 2024, at the age of 66, with loving family members at her side, Satyavathi merged in Arunachala Bhagavan. She is survived by her son, Karamsetty Venu Madhav and her two daughters, Madhuri and Radhika. Devotees will remember her as a kind-hearted, gentle-natured devotee of Bhagavan Ramana.—

Ramanasramam Gardens Up Close

Photographing Ramanasramam’s flower garden at close range is a captivating way of exploring and appreciating the intricate world of small animals, plants, and insects in our midst. Macro-photography allows us to observe details that are typically overlooked. Macro-photographers can capture the vibrant colors and diverse textures of various flowers and foliage, creating a visual feast of nature’s complexity and beauty. The Ashram’s gardens have grown and expanded in recent years, owing in part to Ashram beekeeping which enhances productivity by virtue of bee-assisted pollination. Capturing the garden’s life at close range not only creates stunning visual images but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the small wonders of nature. It’s a reminder of the complex, interconnected world that exists right under our noses, inviting us to observe the unseen beauty that surrounds us every day. Among the flowers pictured in this issue are the Yellow Butterfly Flower (Turnera Ulmifolia) and the Peacock Flower (Caesalpinia pulcherrima). Also pictured here are the Tamil Stagmomantis (cover insert) and the Brown-Bearded Dragon Lizard (above). — [Long-time Ramana devotee, Sergey Filatov is an accomplished interdisciplinary artist now dwelling in Ramana Nagar. To view his work, see the following: https://vimeo.com/761388160.]

Announcement: Daily Live Streaming

Ramanasramam is live streaming the Tamil Parayana and Vedaparayana each day, Mon-Sat, 5-6.45 pm IST. To access Ashram videos, go to: https://youtube.com/@SriRamanasramam/videos

Endnotes

- 1 “Ramana Gives Rama-Darsan”, TKS, Call Divine, vol. 8, p. 216-219.

- 2 “Bhagavan’s Writing”, Mountain Path, 1966, pp. 40-41; also see: “Sri Ramana Nool Thirattu”, Mountain Path, Jayanti 2000, pp. 194-195. p. 3.

- 3 “Sri Ramana Gives Rama-Darsan”, Call Divine, vol. 8, p. 216-219.

- 4 “Deepavali Darsan” from At the Feet, pp. 24-26; TKS adds to this segment: A similar experience is recorded by the Buddhist Lama Anagarika Govinda in his Foundations of Tibetan Mysticism, quoting the experience of Baron Dr. Valtheim-Ostaur: ‘While my eyes were immersed in the golden depths of the Maharshi’s eyes, something happened which I dare describe only with the greatest reticence and humility in the shortest and simplest words, according to truth. The dark complexion of his body transformed itself slowly into white. This white body became more and more luminous, as if lit up from within, and began to radiate. I saw him sitting on the tiger-skin as a luminous form. This was no rare occurrence in the life of devotees; though Bhagavan himself would have playfully dismissed it, with all other observed wonders of the senses, with “It’s all in the mind!”. Yes, that is true, but how many of us can see such beauties in the mind in place of the ugly and commonplace which obsess it all the time?

- 5 At the Feet, p. 7.

- 6 Ibid., p. 7.

- 7 Ibid., p. 8/a>

- 8 Ibid., p. 8.

- 9 Ibid., p. 9.

- 10 Talks, §195

- 11 Alfred Houseman

- 12 Talks, §241.

- 13 Talks, §13.

- 14 Breakthroughs in early life trauma research are made readable for the layperson in books like Pete Walker’s Complex PTSD and Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps Score, as well as in research of the neuropsychologist, George Bonano who focused his 35-year career on stress and anxiety research.

- 15 Talks, §41.

- 16 Talks, §80.

- 17 Talks, §202.

- 18 Talks, §146.

- 19 Talks, §91.

- 20 Tao Te Ching.

- 21 From the Pi Yen Lu.