The Mountain Path is the official journal of Sri Ramanasramam, Tiruvannamalai.

Mountain Path is dedicated to Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi

Mountain Path - Founded 1964 By Arthur Osborne

Editor: Dr. Venkat S. Ramanan, President, Sri Ramanasramam

This is the web version of the 'Mountain Path' Journal

The aim of this journal will be to set forth the traditional wisdom of sanatana dharma with emphasis on Vedanta, as testified and taught by the great sage Sri Ramana Maharshi, and to clarify his path for seekers in the conditions of our modern world.

CONTENTS

- Divine Names Of Arunachala

- From the Editor’s desk

- Upadesa Undiyar in our Daily Life - S. Ram Mohan

- Essence of Sri Ramana Paravidyopanishad - V. Krithivasan

- Fulfilment of Desires - M.R. Kodhandram

- Self-Enquiry: Some Objections Answered - D.E. Harding

- Muruganar In His Own Words - Hari Moorthy

- Keyword: Na Saṁśayaḥ: The End of Doubt - Part Five - B.K. Croissant

- Sri Bhagavan Ramana Maharshi’s Darshan - Uma Shankar

- Exploring Your ‘Self’ - S. Madhusudhanan

- Vedanta in a Nuts hell: Śankara’s Vedanta Ḍinḍima - I.S. Madugula

- The Paramount Importance Of Self Attention - Sadhu Om

- Poem: On Freedom - Suresh Kailash

- Tamil Siddhas: Konganar - P. Raja

- Maha Bhakta Vijayam: The Blessed Life Of Sant Jayadeva - Nabaji Siddha

- Advaita Primer: Analogies-1 - M. Giridhar

- Nondi’s Corner and Youth Corner

- Question & Answer

- Book Review

Divine Names of Arunachala

34. |

ॐ त्रिनेेत्रााय नम: |

Om trinetrāya namaḥ |

|

‘Tri’ means ‘three’ and ‘netra’ means ‘eye’. |

According to the Mahabharata, the third eye burst forth from Siva's forehead with a great flame when his wife placed her hands, playfully, over his eyes after he had been engaged in austerities in the Himalayas. The frontal eye, the eye of fire, looks mainly inward. Directed outward, it burns all that appears before it. With it, Siva reduced Kama, the god of love, to ashes when he dared to inspire amorous thoughts of Parvati while he was engaged in penance.

The eye of fire can also destroy thoughts. This has been experienced and documented by countless devotees who have received silent initiation from Sri Ramana Maharshi. Arthur Osborne, one of the foremost devotees of Bhagavan during his lifetime, gives his own account:

"Bhagavan was reclining on his couch and I was sitting in the front row before it. He sat up, facing me, and his narrowed eyes pierced into me, penetrating, intimate, with an intensity I cannot describe. It was as though they said: 'You have been told; why have you not realised?' And then quietness, a depth of peace, an indescribable lightness and happiness. Thereafter love for Bhagavan began to grow in my heart and I felt his power and beauty. I did not at first realise that it was the initiation by look that had vitalized me and changed my attitude of mind. Only later did I learn that other devotees also had had such an experience, and that with them also it had marked the beginning of active sadhana (quest) under Bhagavan's guidance."1

How blessed we are by those eyes of fire!

— BKC

FROM THE EDITOR'S DESK

Bhagavan’s Living Presence

Dear Devotees and Seekers,

In the three years since I assumed the role of President at our Ashram, devotees from around the world have shared their concerns and queries with me. Taking these seriously, I plan to dedicate my initial editorials to addressing the most prominent themes. In this edition, I will address the crucial question that consistently arises: Is Sri Ramana Maharshi a living Guru?

In the invocation verses of His Tamil translation of Dakshinamurti Stotram and Atma Bodha, Bhagavan declares that Dakshninamurti and Adi Shankara are manifestations of the One Self. He asserts that it is Shankara himself, abiding in Him as Ramana Maharshi, who composed the Tamil translation of His Sanskrit works. In verse 8 of His devotional hymn Arunachala Navamanimalai, Bhagavan articulates the purpose of His incarnation in chaste Tamil, stating that Lord Arunachala raised him to His state so that Shiva, as Absolute Consciousness, may flourish.

Bhagavan's descent on earth is aimed to guide us away from seeking God and Guru externally. Instead, he urged us to realise God and Guru as Absolute Consciousness within us through the practice of Atma-Vichara or Self-Enquiry. While Bhagavan emphasised the necessity of a Guru, he constantly reiterated that God, Guru, and Self are one and can be found within ourselves. In His words, "The Guru is both 'external' and 'internal'. From the 'exterior', he gives a push to the mind to turn inward; from the 'interior', He pulls the mind towards the Self and helps in the quieting of the mind. That is guru kripa (grace). There is no difference between God, Guru, and the Self."

Even when Bhagavan was in the body, He never identified Himself with it. He consistently directed devotees to turn inward and find Him as their inner Guru. During His last sickness, when devotees spoke as if He was forsaking them and pleaded their weakness and continued need for Him, He retorted, "You attach too much importance to the body." In this simple yet profound response, Ramana Maharshi redirected the focus of His devotees from the physical form to the formless Self, emphasising the timeless nature of the Self beyond the transient existence of the body. The statement encapsulates the core teaching of Advaita Vedanta — the recognition of one's true identity as the eternal, unchanging consciousness.

Ramana Maharshi's response serves as a reminder that the Guru is not confined to the physical form and that the true essence of guidance lies in the formless, eternal Self. It echoes the Advaitic understanding that the ultimate reality is beyond birth and death, and the Guru's presence is always available in the Heart of the sincere seeker.

Bhagavan was not one to promise future returns or appointed successors. Instead, Sri Bhagavan firmly declared, "I am not going away. Where could I go? I am here." This assertion transcends the limitations of time, reflecting the Sadguru's realisation of the eternal 'Now' and becomes an invitation to turn inward and recognise the eternal presence within, as guided by the sage's timeless teachings. The concept of 'here and now' in Advaita Vedanta emphasises the timeless and eternal nature of the ultimate reality, Brahman. It encourages individuals to recognise the illusory nature of time, live fully in the present moment, and realise the true nature of the Self beyond the limitations of past and future. The teachings also give an assurance that Bhagavan is ever available to guide us in all these endeavours.

Can we not all testify to this? Do we not feel His radiant presence at His Ashram and within us? Soon after His Mahasamadhi in 1950, devotees shared that they felt even deeper peace and joy at His samadhi and in their spiritual practice. Arthur Osborne, the founder editor of Mountain Path, says, "More than ever He has become the Inner Guru. Those who depended on Him feel His guidance more actively, more potently now. Their thoughts are riveted on Him more constantly. The vichara, leading to the Inner Guru, has grown easier and more accessible. Meditation brings a more immediate flow of Grace."

Bhagavan, who is compassion incarnate, has left us His Ashram and His beloved Arunachala as external spiritual reinforcements. A visit to His Ashram and performing Girivalam around the sacred hill fill us with enthusiasm and devotion to strengthen our sadhana. He has also left us His precious teachings, condensing all that is needed for the seeker in simple language with utmost clarity. 'Who am I?', the small booklet, contains the essence of His teaching. The brevity and clarity of each response to the 28 questions in the book are so refreshing that repeated study of this one work will alone suffice. Bhagavan has therefore left behind all that we need for external support — His Ashram, the Arunachala Hill, and His precious teachings.

Once we take refuge in Bhagavan and surrender ourselves to Him, we experience profound joy, as if we have come home. The deep sense of peace eradicates any remaining desire to seek another teacher, whether alive or otherwise. A feeling of completeness inspires us to earnestly practise His teachings, as we have full faith that this alone will lead us to the goal. The gradual elimination of the urge to seek external help is, in itself, a significant gain for sincere devotees. I often meet devotees who express their gratitude to Bhagavan for rescuing them from financial and emotional distress involved in searching for and following other teachers — individuals who are gifted, charismatic and learned but are not Sadgurus like Bhagavan. Frequently, such teachers make extensive demands on devotees in the name of 'service,' encompassing both physical and material obligations, thereby affecting their personal relationships and domestic peace. In stark contrast, Bhagavan demands nothing of us. He only wishes us to follow His teachings and strive sincerely in our practice. Following Bhagavan's teachings brings unmatched clarity into our lives. His grace takes care of our external circumstances, making them harmonious and conducive to our spiritual practice

As administrators of His Ashram, we are the beneficiaries of our staunch faith in His living presence. We know that He runs the Ashram, and we are simply His instruments. This is not a sentimental theory; we experience this every moment of each day.

Our role is to be sincere caretakers of His Ashram and His teachings. By strictly focusing on administration and not acting as intermediaries between devotees and Bhagavan, we strive to ensure that all devotees, irrespective of gender, caste, race, or nationality, can feel Bhagavan's living presence directly without any intervention. That is why there are no human teachers at the Ashram.

We are dedicated to preserving the teachings in all their purity. We will make them available in the principal languages of India and across the globe, in both print and digital formats. The publications team leverages the power of social media to reach devotees in every corner of the world and deliver the essence of Bhagavan's teachings to their digital devices.

The truth is that no one can give us liberation. The way can be pointed out, directions can be given. In His response to the question, 'Is it not possible for God and the Guru to effect the release of a soul?' in 'Who am I?,' Bhagavan says clearly, "God and the Guru will only show the way to release; they will not by themselves take the soul to the state of release. In truth, God and the Guru are not different. Just as the prey which has fallen into the jaws of a tiger has no escape, so those who have come within the ambit of the Guru's gracious look will be saved by the Guru and will not get lost; yet, each one should by His own effort pursue the path shown by God or Guru and gain release. One can know oneself only with one's own eye of knowledge, and not with somebody else's. Does he who is Rama require the help of a mirror to know that he is Rama?" Only a Sadguru like Bhagavan can respond with such unambiguity. Our intense earnestness and total dedication to the goal are the most essential factors. We simply need to attend to making ourselves ready, and the rest is automatic. Sri Ramana Maharshi did not live for His time alone. His presence and guidance can be experienced now, just as when He was physically present. Those who turn to Him with sincere aspiration and longing, those who try their best to apply His teachings, will feel His grace and guidance. There is no doubt about this.

In humility and devotion,

Venkat S. Ramanan

Upadesa Undiyar In Our Daily Life

S. Ram Mohan

Dr. S. Ram Mohan is the author of numerous articles on Bhagavan’s teachings and is currently the editor of Ramanodhayam, the Tamil magazine of the Ramana Kendra in Chennai.

In our daily life, we go through the state of waking, dream, and sleep. Our true nature of ‘I am’ is ‘how we remain in our sleep’ (blissful, sugam in Tamil) Jagrat Shusupti. Why? In sleep, we lose our identity due to the shutdown of our senses and mind; yet the subtle awareness ‘I am’ (unarvu in Tamil) remains. Thus on waking up, we could say, if we had a good sleep or not.

The true nature of ‘I am’ is the Self and it is blissful. In both dream and waking states, the mind becomes active and falsely identifies ‘I am’ as an individual body; leading us to have both physical and mental experiences involving both the body and worldly objects. Furthermore, such a false identification of ‘I am’ with an ‘individual body’ makes us lose our inherent state of bliss.

During the dream state, our mind is not capable of regulating our experiences. Thus both enjoyable and miserable experiences are inevitable. However, when we are in the waking state, such dream experiences generally are forgotten or ignored, which means the dream experience is not carried further.

During the waking state, our mind is capable of regulating our experiences through study of the mind and its control and being alert, etc. To attain a blissful life, we must hold firmly onto a single thought ‘I am the Self’, which is our true identity; and should lead our lives accordingly. This attitude will enable us to face any challenges in our life that happen due to our prarabdha, without losing our peace and happiness.

Based on the essence, from the verses of ‘Upadesa Undiyar’, the explanations for the above observations are provided in a question and answer form.

Question: Could you briefly describe an individual’s life?

Answer: An individual’s life is a collection of daily occurring events between birth and death. The daily life of each individual is unique but comprises the three states. Waking state, dream state and sleep state.

1 The ever present true nature of an individual being ‘I am’ is ‘how an individual remains in sleep’. The reason being that although in sleep an individual loses the

identification with the body due to the shutdown of one’s senses and mind the subtle awareness ‘I am’ remains (based on verse 21). 2 Thus an individual on waking up could say

whether he had a good sleep or not.

Unarvu is subtler than thought. Unarvu is omnipresent, that is during waking, dream and sleep and it is ‘I am’. As Unarvu is selfevident, it can be felt by all. It is beyond description and it is not demonstrable (based on verse 23). 3

Unarvu is neither conscious nor unconscious. It is beyond comprehension (based on verse 27). 4 For more details about unarvu, please refer to the footnote 7, ‘Self’. Immediately on waking up, while still in bed, one should not let the thoughts of the world rushing, remaining in a state of ‘No thoughts’. Thereby, an individual can understand the true nature of ‘I am’ (unarvu), which is present during deep sleep. 5 After waking up, an individual mind becomes active and starts to experience both the physical body and the physical environment (world), causing the bliss to fade away.

Question: If the true nature of an individual is ‘I am’ and is the state of ‘how an individual remains in sleep’; then what about during both dream and waking states?

Answer: The true nature of the Self is ‘I am’ and it is a state of bliss. In both the dream and waking states, the mind becomes active and falsely identifies ‘I am’ with the individual body; leading an individual to

have physical and mental experiences, involving both the body and the worldly objects. The inherent bliss is thus lost. Thus an individual’s experience relying on the false identification of ‘I am’ with ‘an individual body’; leads to

the loss of our inherent state of ‘Ananda’. Such a false identification of the mind happens automatically for each individual unless one is vigilant.

The nature of experiences distinguish the human life from any other earthly life.

Question: Is it possible for an individual to be in bliss during both dream and waking states?

Answer: During the dream state, an individual mind is not capable of regulating the experiences. Thus, for an individual, both enjoyable and miserable experiences are inevitable. However, an individual is able to

recover easily from the dream experience, once the individual switches to the waking state. In the waking state, an individual simply forgets or ignores the dream experience as it is only a dream and the experience is fully within an

individual.

During the waking state, an individual mind is capable of regulating the experience through the study of the mind, mind control and following spiritual practices.

To experience bliss during the waking state, an individual should investigate the mind first; not to worry about investigating either the body or the world. Why?

It is true for all that the experience of an individual body and world disappears during the sleep state as the active state of the mind is suspended; the experience appears only during the waking and dream states as the mind becomes active.

Thus we can infer that an individual mind is the cause for all our experiences. Causing the individual to experience both the body and the world. Therefore to regulate an individual experience, one should first investigate the mind, its source, its reality.

This is the correct approach to attain our true nature (based on verse 16). 6

Question: What is the nature of mind? How to deal with the mind in the waking state?

Answer: The following are based on the verses 18, 19 and 17: The mind consists of a multitude of linked thoughts. Of the linked thoughts,the root thought is ‘I’, a thought about ‘I am’. The other names for ‘I am’ are:

the Self, 7 Unarvu, Atman, Brahman, Ishvara, the Creator, etc.

With the root thought ‘I’, the next thought of ‘individual body’ is generated automatically and linked. 8 Thus the combined thoughts represent ‘I am the body’ and is called mind (based on verse 18). 9

Why is such an enactment of the mind not appropriate? ‘I am’ is the sentient object. ‘Individual body’ is an inert object. ‘I am the body’ is called mind. It is made of linking the thoughts of sentient and inert objects. It is like covering the chocolate with a wrapper. 10

Hence the thought ‘I am the body’ is called the ego-mind, 11 or the impure mind (based on verse 19). 12

Note: The thought ‘I am the body’ is just the beginning of the experience. For an experience to happen, using the thought ‘I am the body’, the mind generates various thoughts, based on the individual’s vasanas and links them. Thus the mind is the multitude of linked thoughts. 13

As an individual’s waking state experience is based on the ego mind (false identity) and it blocks the inherent bliss, an individual should simply ignore the waking state experience like the dream experience. That is, an individual should ignore both enjoyable and miserable experiences of the waking state and maintain a state of equanimity. This equanimity can be achieved only through the unconditional acceptance 14 of the happenings in one’s life. Indeed, this is the direct way to attain the blissful life during the waking state (based on verse 17). 15

However in social life, it is hard for an individual to simply ignore the waking state experiences like the dream experiences. An individual is expected to react and deal with the people around appropriately, as a part of normal living. To experience bliss during the waking state, an individual has to develop a pure mind to overcome the natural ego-mind.

A pure mind means holding firmly on to a single thought ‘I am the Self’ (the true identity of an individual, the thought ‘I - I’, aham spurippu) and should lead life accordingly (based on verse 20). 16 To keep the pure mind firmly and lead the life accordingly, an individual should study the Self and know the nature of the Self clearly.

Question: What is the nature of the Self? How to keep the pure mind firmly and lead life accordingly?

Answer: The following are based on the verses 22, 24, 25, 26, 28, 29: ‘I am’ (the Self) 17 is permanent and never changes. The life-force, mind, body,

world and experience are momentary, constantly changing. However ‘I am’ is permanent. (based on verse 22). 18

Heart exists as a single unit, having both the Self and the causal body. The Self (Brahman) is ever free from any thought. In the presence of the Self, the causal body (jiva, ignorance) always functions through the mind and always thinks (based on upadhi). 19

When the jiva realises that the functions of the mind are due to the presence of the Self and have nothing to do with the body, it understands and accepts the idea ‘I am the Self’ instead of ‘I am the body’. Thus with the firm conviction ‘I am the Self’, the jiva comprehends the life happenings and leads the life as it is led (based on verse 25). 20

The comprehension ‘I am the Self’ is true. The comprehension ‘I am the body’ is false. Thus during the waking state, the jiva should comprehend the happenings in life through the pure mind (‘I am the Self’) and live accordingly (based on verse 26). 21

The jiva knows that one’s Heart is the cause for the individual life experiences of both the body and world. Hence the jiva comprehends and deals with the prarabdha happenings in life accordingly.

For example, during the day: The jiva, with its ego-mind, believes that the sun is the cause for the individual’s experience of light. The jiva believes, that the sun reaches an individual’s eyes through its rays.

The jiva, having the pure mind knows that the individual’s Heart is the cause for the individual’s experience of light. Further the variation of an individual’s light experience is the cause for the experience of the sun’s rays and the sun.

The true nature of ‘I am’ is free from all experiences, in the sleep state. Thus the jiva knows clearly the individual’s true nature, the differences between the pure mind’s way of living and the ego-mind’s way of living. Hence during the waking state, the jiva should stay established firmly in a steady state of bliss. (based on verse 28). 22

Please stop ruminating with thoughts such as, ‘I am ignorant and I have to find a path to liberation’ etc. Stay always with your true nature, which is bliss, peace, happiness, etc. Indeed, this is called staying at the feet of the Lord, great tapas, service to the Lord, etc. (based on verse 29). 23

Question: During the waking state, how does an individual act and deal with situations harmoniously?

Answer: During the waking state, an individual’s prarabdha decides the happenings in the individual’s life. Such happenings are automatic and are beyond an individual’s control.

With effort, an individual can react to prarabdha happenings. Such reaction is called akamya karma.

Note: An individual action (karma), on its own cannot bestow its fruit to the individual; as the action (karma) is inert. Only the Lord ordains the fruit of an individual’s action to the individual (based on verse 1). 24

Akamya karma can be either checked through the thought process (enquiry) or unchecked (instinct). Unchecked akamya karma could lead to expansion of reactions like an ocean (based on verse 2). 25

Checked akamya karma can be regulated either for good or bad. When akamya karma is performed through the pure mind (the firm conviction ‘I am the Self’), it is called nishkamya karma. Thus nishkamya karma is devoted to the Lord as the Self and the Lord are the same. For an individual, such nishkamya karma will show the way to liberation (based on verse 3). 26

An individual with a cultivated pure mind, having the firm conviction ‘I am the Self’, treats all the living beings (people, animals, birds, plants...) and non-living beings with equanimity. The pure mind is called sattva guna, sat-bhavana and is the same as para bhakti (based on verse 9). 27

An individual having a disturbed mind, can quieten the mind through breath control (based on verse 11). 28 The reason is that the Self is the source for both breath and mind (based on verse 12). 29 Once the mind is settled through breath control, release the mind with the firm conviction ‘I am the Self’. Such practice eventually will overcome the ego-mind (based on verse 14). 30

Note: The adopted texts from the book ‘Who am I? ’ follow: In order to realise the inherent and untainted happiness, which indeed an individual daily experiences when the mind is subdued in sleep, it is essential that an individual should know ‘I am the Self’ during the waking state and lead his life accordingly.

During waking state, the thought ‘I am the Self’ will destroy all other thoughts, and like the stick used for stirring the burning pyre, it will itself in the end get destroyed. Then, there will arise Liberation 31 (Self-realisation); due to the Lord’s Grace.

Essence of Sri Ramana Paravidyopanishad

Part 1 – End of Suffering

Annotated by V. Krithivasan

Mr. V. Krithivasan is a highly accomplished author of many articles and was the editor of Ramana Jyothi, the magazine of the Ramana Kendram in Hyderabad. He has been associated with the Kendram in various capacities for over forty years.

Background

Lakshmana Sarma, the author of this great work on Bhagavan’s quintessential teachings, was a lawyer by profession. He was also an erudite Sanskrit scholar and well-versed in the literature associated with Advaita Vedanta. He came to know about Bhagavan Ramana in the late 1920s and paid a visit to him. He was greatly impressed by Bhagavan’s spiritual stature and without any second thoughts, took him as his Guru. He was fortunate to spend more than twenty years in close association with Bhagavan. He spent the remainder of his life translating Bhagavan’s teachings into Sanskrit and commenting on them in English and Tamil. Lakshmana Sarma has explained how translating Bhagavan’s teachings into Sanskrit poetry became a passion for him:

Once when he was sitting in the holy presence of Bhagavan, Bhagavan asked Sarma, “Have you not read Ulladu Narpadu? ” Sarma replied, “ No Bhagavan, I am unable to understand the Tamil”. Though his mother tongue was Tamil, Sarma was not familiar with the classical Tamil used by Bhagavan in his verses. But clever as he was, he saw a golden opportunity presenting itself and said, “If Bhagavan teaches me, I shall learn it.” 1 Bhagavan agreed to give him private lessons on literary Tamil, along with detailed explanations of his verses. The lessons began with a thorough study of Ulladu Narpadu Anubandham (supplementary verses to the main work of Ulladu Narpadu). This consisted of mostly translations that Bhagavan had made of verses from other well-known Sanskrit works like Yoga Vasishtam, Devikalottaram, Srimad Bhagavatam etc. Anubandham provided an interesting background information to Bhagavan’s teachings and Sarma was starting with an area he was already familiar with, namely, traditional Advaita Vedanta.

As the lessons progressed, to make sure that he fully understood what Bhagavan had taught him, he started composing verses in Sanskrit embodying the teachings of Bhagavan. He would submit these verses to Bhagavan to ascertain that his translations faithfully reproduced what Bhagavan taught. Until Bhagavan approved his Sanskrit translation, he went on re-casting and correcting his verses. In this manner, he finished translating all the 42 verses of Ulladu Narpadu. Even after the first translation, he felt impelled to go on revising his Sanskrit translation again and again. In his own words, “ It seemed to me that no amount of time and labour would be too much for achieving the end I had in mind: the preparation of an almost perfect and faithful rendering into Sanskrit of this holy text”. (Observing this, Bhagavan commented that this was like tapas to Lakshmana Sarma). Sarma gave the title Sat Darshana to his Sanskrit translation of Ulladu Narpadu.

At a certain stage of Sarma’s translation activity, Sri Kapali Sastry, a great Sanskrit scholar and a disciple of Kavyakantha Ganapati Muni, visited the Ashram. On coming to know of the Sanskrit translation of Bhagavan’s Ulladu Narpadu, he asked Bhagavan if the translation could be submitted to Kavyakantha who was at that time staying in Karnataka, for his study and revision, if any. Bhagavan agreed to this. Kavyakantha went through the translation rendered by Lakshmana Sarma and instead of merely revising it, he composed an independent rendering, retaining the title Sat Darshana. Bhagavan received this and handed it over to Lakshmana Sarma.

Sarma saw the composition of Kavyakantha and was greatly impressed with the polished style of the poetry. He told Bhagavan with utmost humility that Kavyakantha’s version was better than his own, and so he would stop revising and improving his translation. But Bhagavan did not accept this decision of Lakshmana Sarma’s and strongly suggested that Sarma’s own efforts should continue parallelly. He told Sarma that he could consider employing a longer metre, which would enable him to accurately incorporate the different shades of meaning that Bhagavan brought out in his Tamil verses of Ulladu Narpadu. Bhagavan also encouraged Sarma to write a Tamil commentary on Ulladu Narpadu. Greatly moved by Bhagavan’s encouragement, Sarma continued his efforts. When his Tamil commentary on Ulladu Narpadu was completed, Bhagavan was very appreciative of the substance, style and the full understanding that Sarma exhibited in conveying Bhagavan’s essential teachings. He asked the Ashram management to take up the publication of Sarma’s Tamil commentary on Ulladu Narpadu, saying that everyone felt that this was the best commentary on Ulladu Narpadu.

Sarma’s deep understanding of Bhagavan’s teachings resulted in yet another book in English by name Maha Yoga,which had a huge reception from Bhagavan’s devotees all over the world. It was translated into many languages. Lakshmana Sarma’s Sanskrit rendering of Ulladu Narpadu and Anubandham was published under the title Revelations.

In 1950, after Bhagavan’s Mahanirvana, Lakshmana Sarma decided to translate the notes he had taken during Bhagavan’s tutorials also into Sanskrit verses. These are 701 in number, and they form a systematic presentation of Bhagavan’s teachings, much like the Prakarana Granthams (simplified texts of Advaita Vedanta for propagation) of Adi Sankara, the most noteworthy being Vivekachudamani. He gave this Sanskrit work the title Sri Ramana Paravidyopanishad, meaning, ‘The Supreme Science as taught by Sri Ramana’. As Bhagavan’s teachings are expressions of his own svanubhuti (permanent inherence in the Self), they are fit to be called as an Upanishad. In Sanatana Dharma, knowledge about the world (objective knowledge) is named as apara vidya. Knowledge of the Self is called as para vidya. In this sense, Sri Ramana Paravidyopanishad is the Supreme Knowledge (or Science) of the Self as taught by Bhagavan Ramana. These were published in Call Divine between 1954 and 1957, with translation in English by Lakshmana Sarma.

In this series of articles, a few selected verses that cover the essential teachings of Bhagavan Ramana will be taken up for a deeper study.

Benedictory Verse – Mangala Sloka

अहंस्वसपेण समस्तजन्तोर्विभान्तं अन्तर्विभुमप्रमेयम्।

गुरं गुरुणामजमादिदेवं वन्दामहे श्रीरमणं दयाब्धिम्।।

ahaṁsvarūpeṇa samastajantorvibhāntaṁ antarvibhumaprameyam guruṁ gurūṇāmajamādidevaṁ vandāmahe śrīramaṇaṁ dayābdhim

We bow down to Sri Ramana, the Ocean of Grace, the Infinite, Immeasurable, Unborn Primal Divinity, Guru of all Gurus, shining in the Hearts of all creatures as ‘I’.

It is the tradition to begin works of this nature with an auspicious word. Lakshmana Sarma begins with the word aham, ‘I’. Aham is an auspicious word because it is the first name of God according to Bhagavan.2 Bhagavan quotes from Brihadaranyaka Upanishad: ātmaivedamagra āsīt puruṣavidhaḥ, so’nuvīkṣya nānyadātmano’paśyat, so’hamasmītyagre vyāharat, tato’haṁnāmā-bhavat. “ In the beginning, the Universe was verily the Self, in the form of a person. He pondered and beheld nothing else but himself. He first said, ‘I am he.’ Therefore, he got the name ‘I’. (Br. U. 1-4-1). The understanding that ‘I’ is the first name of the Supreme Being is central to an understanding of Bhagavan’s teachings on the nature of God or the Self as well as the means to gain the ultimate state of deliverance.

Bhagavan Ramana shines in the Hearts of all creatures as ‘I’, says Lakshmana Sarma. Bhagavan himself says the same in his answer to Amritanatha Yogi, who wanted to know who Ramana was:

“In the recesses of the lotus-shaped Hearts of all, beginning withVishnu, there shines as pure intellect (Absolute Consciousness)

the Paramatman, who is the same as Arunachala Ramana. When

the mind melts with love of Him, and reaches the inmost recess of

the Heart wherein He dwells as the beloved, the subtle eye of pure

intellect opens and He reveals Himself as Pure Consciousness.”

When Lakshmana Sarma calls Bhagavan as guruṁ gurūṇām, Guru of Gurus, it is not merely praise. Renowned masters and acharyas of the land visited Bhagavan and bowed down in reverence — Mahan Seshadri Swami, Achyuta Dasa the Hata Yogi, Kavyakantha Ganapati the great tapasvin, Sri Narayana Guru of Kerala, Shankaracharya Bharati Krishna Tirtha of Puri, Swami Sivananda of Rishikesh, Swami Chinmayananda, Paramahamsa Yogananda, Swamis of Ramakrishna Mission and many more. We are reminded of Suka, an atyasrami like Bhagavan, who was referred to as Yoginam Paramam Guru, Supreme Master of Yogis, in Srimad Bhagavatam.

Bhagavan is Aprameya, incomparable; the manner of his Realisation, his permanent inherence in the Self, his absolute lack of body consciousness, his unique method of teaching through Mauna, his utter humility — all these and more, make him a unique, incomparable Guru.

Obeisance to the Guru

ईश्वरो गुरुरात्मेति मूर्तिभेद विभागिने। व्योमवद् व्याप्तदेहाय दक्षिणामूर्तये नमः।। (1)

īśvaro gururātmeti mūrtibheda vibhāgine vyomavad vyāptadehāya dakṣiṇāmūrtaye namaḥ

Obeisance to Sri Dakshinamurti, manifest in the three forms as God, the Guru and the Self, whose form is infinite as the Space.

Lakshmana Sarma begins Sri Ramana Paravidyopanishad with the famous verse of Sureshvaracharya (one of the four disciples of Adi Shankara) which brings out the unity of the three apparently distinct entities, namely, God, the Guru and the Self. Sureshvaracharya composed this as the invocatory verse of his commentary on Adi Sankara’s Dakshinamurti Stotram. Bhagavan Ramana has said that these are the three stages of Divine Grace:

“At some time a man grows dissatisfied with his life and, not content with what he has, seeks the satisfaction of his desires through prayer to God. His mind is gradually purified until he longs to know God, more to obtain His Grace than to satisfy worldly desires. Then God’s grace begins to manifest. God takes the form of a Guru and appears to the devotee, teaches him the Truth and, moreover, purifies his mind by association with him. The devotee’s mind thus gains strength and is then able to turn inward. By meditation it is further purified until it remains calm without the least ripple. That calm expanse is the Self. The Guru is both outer and inner. From outside he gives a push to the mind to turn inward while from inside he pulls the mind towards the Self and helps in quieting it. That is the Grace of the Guru. There is no difference between God, Guru and the Self.”3

Natural State

माण्डूक्यमुख्योपनिषत्सु दिष्टा ज्ञानाभिधा या सहजात्म निषठा। ससाधना तेन निजानुभूत्या सन्दर्शिता सा प्रतिपाद्यतेऽत्र।। (2)

māṇḍūkyamukhyopaniṣatsu diṣṭā jñānābhidhā yā sahajātma niṣṭhā sasādhanā tena nijānubhūtyā sandarśitā sā pratipādyate’tra

Herein is expounded the teaching about the Natural State of the Self, which is Pure Awareness. The same teaching which was revealed in the ancient scriptures like Mandukya and other principal Upanishads, is imparted again (by our divine Guru) based on his own experience, along with the means to reach that State.

Lakshmana Sarma makes the intent or purpose of this book known at the outset – it is to systematically explain the teachings of Bhagavan Ramana, which are the expressions of his own experience. These teachings happen to be in total conformity with ancient scriptures, the Upanishads. Sarma is implying that the Divine Guru is One, who manifests again and again from the ancient to the modern times, to lead the ignorant masses to the supreme goal of abiding in the Natural State of pure Awareness.

Lakshmana Sarma picks out Mandukya Upanishad for a reason – the emphasis on mano nasa (the destruction of the mind) as the ultimate goal is notable in Bhagavan’s teachings as well as in Mandukya Upanishad. This Upanishad uses a different word, viz., prapanchopasamam which means: cessation of the world (which implies cessation of the mind that sees the world). This occurs in the seventh mantra of this shortest of all Upanishads. Just as Bhagavan refutes the relative Consciousness associated with the three states of waking, dreaming and deep sleep as unreal and illusory, the first part of this mantra negates all relative states of Consciousness and in the second half brings out the real nature of Atman.

“That which does not cognise either internal objects, or external objects, which is not a mass of Consciousness, which is neither cognitive nor non-cognitive; that which cannot be seen, which cannot be described, which cannot be grasped, which has no distinctive marks, which cannot be thought of, which cannot be designated, that which is of the essence of oneness of the Self, that in which the world ceases to exist, the peaceful, the benign, the non-dual, such is the state of turiya (the fourth state). This is the Atman. That is to be known.” (Mandukya Upanishad, v.7)

Permanent abidance in Turiya (the term used by Mandukya Upanishad) is the same as sahaja sthiti or Natural State, the term used by Bhagavan.

In Muruganar’s Ramana Paada Maalai, there is this beautiful description of the Natural State:

விவகாரம் தன்னிலுமம் மெய்ப்பரத்து ஞானந்

தவறா திருக்கை சகஜமெனும் பாதம் (679)

vivakaaram tannilumam meypparaththu jnanam

tavaratirukkai sahajam enum paadam

Sahaja is that state where one does not slip out of the pure awareness of the Supreme State even while engaged in worldly activities. So says paadam (Sri Bhagavan).

Giving an illustration about the Natural State (Sahaja Samadhi), Bhagavan says “Those who are in the Sahaja State are like a light in windless place, or the ocean without waves; that is, there is no movement. They cannot find anything which is different from themselves. But for those who do not reach that state, everything appears to be different from themselves.4

Bhagavan also says, “There is no creation in the state of Realisation. When one sees the world, one does not see oneself. When one sees the Self, the world is not seen. So see the Self and realise there has been no creation.”5 This extraordinary statement about non-creation of the world is another similarity between Bhagavan’s teachings and the teachings of Gaudapada, the commentator on Mandukya Upanishad. Bhagavan had always been an uncompromising Advaitin in his teachings and this work brings this out in all its grandeur. Sarma says that the sadhana, the method that Bhagavan teaches for gaining the Natural state is the same that he himself followed and became enlightened. Therefore, Bhagavan recommended Self-enquiry as a primary means for Self-Realisation.

If you know yourself, there will be no suffering

Our spiritual journey begins with an acute awareness of imperfection in the world around us or with a sense of discontent or mental suffering. When the realisation dawns that there is no scope of obtaining perfect happiness unmixed with miseries from this world, one becomes fit for discipleship. Such an aspirant should approach a Guru who has freed himself totally from the shackles of samsara and who is peaceful. Such a Guru, on being approached with reverence, will reveal the secret of happiness thus:

व्रूयात् स बुद्धः परमं रहस्यं समस्तवुद्धानुभवप्रसिद्धम्।

जानासि चेत् स्वं न तवास्ति दुःखं दुःखी भवेस्त्वं यदि वेत्सि न स्वम्।। (4)

brūyāt sa buddhaḥ paramaṁ rahasyaṁ samastabuddhānubhavaprasiddham

jānāsi cet svaṁ na tavāsti duḥkhaṁ duḥkhī bhavestvaṁ yadi vetsi na svam

The Sage will reveal the Supreme Secret, confirmed by the experience of all the Sages: “If you know yourself, there is no suffering for you. If you suffer it only means that you do not know yourself.”

According to Advaita Vedanta, suffering is caused by ignorance of one’s real nature which is Sat-Chit-Ananda, Existence-Consciousness-Bliss. This ignorance takes the form of ego which has put limitations on itself. Bhagavan says, “The cause of the misery is not in the life outside you; it is in you as the ego. You impose limitations on yourself and then make a vain struggle to transcend them. All unhappiness is due to the ego. If you deny the ego and scorch it by ignoring it, you would be free. To be the Self that you really are is the only means to realise the bliss that is ever yours.”6

Whenever we are assailed by unhappiness, we must remember that unhappiness is not natural to us and turn our attention away from this mind-identified state towards the I-sense, in an effort at Self-enquiry. Moreover, our daily experience of freedom from suffering offers a great clue, as is brought out in the next verse.

यतः सुषुप्तौ न तवास्ति दुःखं त्वदीयमारोपितमेव नान्यत्।

जिज्ञासया स्वं समवेत्य सत्यं निजस्वस्पे सुखरूप आस्स्व (5)

yataḥ suṣuptau na tavāsti duḥkhaṁ tvadīyamāropitameva nānyat

jijñāsayā svaṁ samavetya satyaṁ nijasvarūpe sukharūpa āssva

“Since you have no suffering in deep sleep, this suffering is only falsely ascribed to your Self. Realise the Truth of yourself by the resolve to know it and remain in that state which is bliss itself.”

Suffering belongs to the mind alone. Only when the mind operates, suffering is felt. In the state of deep sleep, where the mind is absent, suffering is not experienced. Bhagavan would repeatedly draw the attention of seekers to this everyday experience of everyone. In fact, as one goes through ‘Talks with Ramana Maharshi’, one cannot help but notice that Bhagavan took this line of approach to explain Reality most of the times. Just as ‘Who Am I?’, ‘What was your experience in deep sleep?’ (or a variation of this), was a powerful weapon in Bhagavan’s arsenal. Here is a typical conversation:

Q: Worries of worldly life trouble me much and I do not find happiness anywhere.

M: Do these worries trouble you in sleep?

Q: No.

M: Are you the same person now as you were in sleep, or are you not?

Q: Yes.

M: So it proves that the worries do not belong to you.7

Bhagavan is pointing out that whenever the mind becomes still, as it does in deep sleep, one will be able to transcend suffering. Deep sleep state is temporary and the mind emerges from it after some time. Moreover, the stillness and the consequent freedom from worries and suffering is experienced unconsciously in deep sleep. When the stillness of sleep is experienced with full awareness, it will be samadhi or Turiya. The Jnani abides permanently in the state of turiya, by destroying the mind. In this way, he has freed himself once and for all from suffering of all kinds.

MOUNTAIN PATH

Statement about ownership and other particulars about Mountain Path (according to Form IV, Rule 8, Circular of the Registrar of Newspapers for India).

1. Place of Publication – Tiruvannamalai; 2. Periodicity of its Publication – Quarterly; 3. Printer’s Name – Sri. N. Subramaniam; Nationality - Indian; Address – Sudarsan Graphics Private Ltd., 4/641, 12th Link Street, 3rd Cross Road, Nehru Nagar, Kottivakkam (OMR), Chennai 600 041; 4. Publisher’s Name – Sri. Venkat S. Ramanan; Address – Sri Ramanasramam, Sri Ramanasramam PO., Tiruvannamalai 606 603; 5. Editor’s Name – Sri. Venkat S. Ramanan; Address – Sri Ramanasramam, Tiruvannamalai; 6. Names and addresses of individuals who own the newspaper and partners or shareholders holding more than 1% of the total capital – SRI RAMANASRAMAM, Tiruvannamalai.

I, Venkat S. Ramanan, hereby declare that the particulars given above are true to the best of my knowledge and belief. 31/03/2024

Fulfilment of Desires

M.R. Kodhandram

M.R. Kodhandram is a postgraduate from the IIT Madras. He has lived in Tiruvannamalai for the past 22 years and has published two commentaries in English on Andal’s Tiruppavai and Bhagavan’s Upadesa Saram. He has also written commentaries in English on Bhagavan’s Bhagavad Gita Saram, Atma Bodha, Aksharamanamalai, Dakshinamurti Stotram and Guru Stuti, and the great Tamil scripture Tirukkuṛaḷ

We have created numerous desires in our life right from our childhood. Some have been fulfilled and the rest still remain in us awaiting fulfilment. There are also the unfulfilled desires carried forward from the previous births. The desires that exist in us (in our soul in the Heart) rise up every now and then in our mind urging us to fulfil them. Till they are fulfilled, the mind will be restless and we cannot concentrate on other matters. The more the intensity of the desire, the greater its pressure on us. What happens when the desire is fulfilled? There will be satisfaction and the mind will get peace. For instance, I have a strong desire to eat ice cream. It will keep rising in my mind as a thought and will gather intensity until I fulfil it. As soon as I eat the ice cream, the desire ends and I feel happy and satisfied for the time being. Why do I feel happy on fulfilling the desire? Bhagavan says that the mind after fulfilling a desire goes back to its source and experiences the happiness of the Self. But due to ignorance, we think that we obtained this happiness by eating the ice cream. The happiness we get through the objects of the world is known as pleasure. Thus an imprint of pleasure gets stored on our soul for ice cream. This causes the desire for ice cream to keep rising every now and then and we try to fulfil it.

Supposing we eat two or three ice creams, thinking about the pleasure we got, it may result in an upset stomach or a throat infection, which will give us pain. If pleasure were to really exist in the ice cream, then eating three ice creams should give us three units of pleasure. But the pleasure we get in eating the second ice cream is less than that of the first one. Eating the third ice cream will give us even lesser pleasure. This is the Law of Diminishing Marginal Returns in economics. After the third ice cream, we no longer wish to eat more ice cream as we super health consequences. Thus, all pleasures eventually lead to pain. This is the plan of Nature so that we may outgrow our desires and develop contentment. Having no desires is the best state of mind! We should realise that the pleasure is not in the object but in the intensity of our desire. See how a dog derives pleasure even from a dry bone. It soon enjoys tasting its own blood as the bone pricks its mouth. Thus, when the desires are eradicated, no one will find the objects of the world pleasurable.

Thus we should realise that there is NO inherent happiness or pleasure in any object of enjoyment. Bhagavan says that we imagine, through our ignorance, that we derive happiness from objects. Actually, when the mind goes out towards the objects of the world, it only experiences misery as we are going away from the Self. When an object of desire is obtained, the mind goes back to its source and experiences the happiness of the Self. Bhagavan says that this is like a person who goes out into the hot sun in search of some object of desire. After obtaining this object, he comes back to the cool shade and rests there in happiness. Again and again, desire makes him leave the cool shade and venture out into the hot sun. In contrast, Bhagavan says, a wise man stays in the shade. Thus desirelessness is wisdom. The mind of the wise does not go out towards any object of desire and his happiness is not dependent on external things. Only when we attain this vairagyam (desirelessness or detachment), will we be able to internalise the mind and take it to its source within to realise our true Self.

This teaching of Bhagavan’s is very relevant in today’s world because we find most people running after material things in order to gain happiness. As the Buddha said, “The more we get, the more we want.” People who want more and more will never be satisfied in life. We should realise that the true and lasting happiness lies only in the Self.

Sage Tiruvaḷḷuvar says in Tirukkuṛaḷ 1 #363, “There is no wealth as great as desirelessness; there is nothing equivalent to it (in merit) anywhere in the world.” In Kuṛaḷ #361, he says, “For all beings, desire is the seed for the never-ending cycle of births.” Therefore, in the next Kuṛaḷ (#362), he says, “If one desires, let it be the desire for not being born again; and that comes about only by seeking desirelessness.”

Thus, desirelessness is the greatest wealth one may wish to acquire as it will pave the way for the attainment of the imperishable wealth of jnana or Self-Realisation. The wealth of money, property or children is transient. The wealth of desirelessness or vairagyam is more precious than any other wealth, because, with this attainment, you will be able to progress on the spiritual path and attain Self-Realisation which will end your birth cycle itself as mentioned in the Kuṛaḷ. If you are desireless you will be contented with what comes to you of its own accord as per your prarabdha. Bhagavan told Devaraja Mudaliar,2 “Do not seek anything unnecessarily. If it comes of its own accord, I do not object to your enjoying it.” In the great scripture Yoga Vāsiṣhṭha, it is said that contentment is the greatest gain. When you seek nothing in this world, you will get everything you need for your life from Nature and you will be peaceful too. Thus, there is no wealth richer than desirelessness.

Desire is like a fire; the more we feed it (with the oil of acquisition and gratification), the stronger it burns and there will be no end to our desires. In the olden days, people were happier because their desires were few and they were content with simple things. Thus, their minds were calmer. Such a mind contributes to good health and success in life.

Let us take an example: suppose we want to go to a movie that has been just released. The mind will be restless till we see the movie. After seeing the movie, the desire is temporarily satisfied and the mind goes back to its source and experiences the happiness of the Self. We then feel happy that we have seen the movie. But ignorance and delusion make us think that our happiness was derived from the movie and hence our desire for movies gets strengthened. There is really no happiness inherent in the movie.It was the absence of desire at the end of watching the movie that actually gave us happiness! Thus desirelessness is the highest happiness. It is found by abiding in the Self. When we realise that happiness rests in the Self, the desire for the objects of the world ceases. Desires arise only because of the wrong understanding that objects contain happiness. When we realise the truth about happiness, the objects of the world cease to attract us. This was how Bhagavan lived his life in Tiruvannamalai, never seeking anything and satisfied with whatever came to him on its own accord.

The great Siddha Tirumular says in his famous work Tirumandiram:

ஆசை யறுமின்கள் ஆசை யறுமின்கள்

ஈசனோ டாயினும் ஆசை யறுமின்கள்

ஆசை படப்பட ஆய்வருந் துன்பங்கள்

ஆசை விடவிட ஆனந்த மாமே. -- #2615

It means,

“Cut off desires, cut off desires!

Except for God, one should cut off all other desires;

The more the desires, the more your sorrows;

The more you give up, the more your happiness shall be.”

[Generally, the second line is misinterpreted by many. In the second line, அயின் means but, except,தவிர; உம் is அசை , an expletive. Thus the second line of the verse means: except for ஈசன் or God, one should cut off all other desires!]

As long as the mind is deluded, it runs after the fleeting joys of the world. Once it tastes the joy ‘in’ an object or person, it gets attracted to it again and again. Thus the desire for an object or person becomes an attachment leading to bondage. Then the mind will cling to the object or person whom it is fond of or who gives joy to it. If the person goes away or the object of desire is lost, then misery will arise as the attachment has externalised the mind. Until the desire is fulfilled there will be sorrow. Attachment is therefore very troublesome. So is our addiction to various enjoyments. We cannot easily give them up, and as the mind seeks to fulfil them, misery arises. Simple desires do not give so much trouble as they rise sporadically and once they are fulfilled, they will go away for a long time.

Simple wishing is like the stroke of a pencil; it can be erased easily. But if we go on deepening the stroke of the pencil by repeatedly writing with the pencil on the same line, the line will get dark and deep. Then you cannot erase it easily. Sankalpas (strong desires) are similar. If you go on wishing for the same thing, the wish becomes strong and you cannot erase it easily. Later on, the wish may possibly be fulfilled, but it will give us pain when the wish is not fulfilled. This is the way Nature makes us outgrow our desires. Thus we have to be very careful about what we wish for. If we cannot fulfil our desires in this lifetime, they will lead to more janmas for us. Thus, our Mukti will be delayed.

How do we overcome our desires? For example, we have the desire to purchase an independent house in a gated community. We had been thinking about this for a long time because some of our friends have purchased such houses. But when we enquire about them in the market, we may find that we cannot afford to buy them. We therefore decide that it is enough to buy a small flat and we settle for that. Thus our desire for an independent house comes to an end. In a similar manner, we can end all our inordinate desires by asking ourselves whether we really need those objects of our desire, what are the pros and cons like whether we have the means to afford, maintain or protect them etc., then we will be able to get the right understanding to decide whether to pursue the desire or let it go. Thus, only a thorough enquiry will take the mind to its roots to destroy the vasanas causing the desire.

Suppose, we are fond of buying clothes and we have not been able to fulfil this desire for a long time because of financial constraints. Then, whenever we get some money, we will go and buy new clothes. Initially, we will thank Bhagavan for giving us the money to buy new clothes. But after a few purchases, Bhagavan’s Grace will make us enquire why we need to constantly buy more clothes when we already have enough clothes. And if we still buy them, our conscience will start pricking us and we will pray to Bhagavan to help us overcome this desire. So the next time we go to buy clothes we will restrict our purchase. If we are used to buying 4 or 5 clothes, we will buy only one or two due to our timely enquiry. If we persist with our enquiry, we will be able to progressively weaken the desire and end it. Then we will buy clothes not out of desire, but only out of necessity. And when we buy new clothes, we will give away some of our old clothes to some needy person. In this manner, we will be able to overcome our desire through enquiry and prayers. Only then will we be able to make our mind subtle, making it suitable for practicing Atma Vichara or Self-Enquiry as taught by Bhagavan. This practice leads us to the discovery of our true Self within, ultimately uniting with it and guiding us towards our supreme goal of liberation.

Thus our desires can be ended only through an understanding based on investigation/enquiry and not through their suppression. A desire does not end merely by renouncing the object of desire. The desire itself has to be rooted out by destroying the vasanas through sadhana and enquiry. Thus rejecting the object of enjoyment is the first step and renouncing the desire is the final step.

As we enjoy the object of desire, if we enquire into the desire in a thorough manner — we should see whether we require it and how it lowers our mind etc. — the desire will automatically weaken. If we persist with this enquiry each time a desire manifests, the vasanas or seeds of our desires will get progressively weakened and, eventually, destroyed. This is the power of enquiry which Bhagavan has taught us. But, if we do not enquire in our mind at the time of fulfilling a desire, the desire will get strengthened, and it will keep rising again and again. In Upadesa Saram, verse 2, Bhagavan says, “The result of action (performed for the fulfilment of a desire) will on completion, leave seeds that would push you into an ocean of (similar) actions (in the future), and (this) will not fetch you Liberation (as vasanas strengthened will lead to rebirth).”

Thus, we should try to overcome all our desires through timely enquiry, prayers and surrender to Bhagavan. Does it mean that we should never enjoy anything in life? Bhagavan says, “As a general rule, there is no harm in satisfying a desire where the satisfaction will not lead to further desires by creating vasanas in the mind.” In this aspect, Bhagavan also says, “Small desires such as the desire to eat, drink and sleep and attend to calls of nature, though these may also be classed among desires, you can safely satisfy. They will not create new vasanas in your mind, necessitating further birth.”3

Why do some of the desires refuse to end, even on repeated enquiry while some end on enquiry? What is the rule? If the desires are strong and deep-rooted, they will not go away by just an enquiry. They are probably there over the janmas. However, we must keep praying strongly and enquiring as and when we are affected by them. Our regular prayers and enquiry will put an end to our desires after we fulfil them to some extent. Then the vasanas would have weakened and we will be able to overcome them.

The purpose of prayer is also to help us remember not to indulge in the desire when we are faced with a situation wherein we are likely to get tempted. The prayer will give us the strength of mind to let go. Thus, through enquiry and prayers, we have to overcome all our desires and attachments. There are no shortcuts. We should realise that there is no unalloyed joy in the objects of the world. Pleasure always ends in pain. The mind realises this fact after repeated suffering over janmas. Then it will turn away from all pleasure-seeking and seek the path of steady peace that lies within, away from the world of dualities. This is the state of vairagyam (non-attachment) which comes through discrimination or vivekam. In order to progress on the Spiritual Path, we should start giving up our desires one by one with sense control and understanding, and develop some vairagyam. Otherwise, we cannot progress on the Path. Worldly desires will only take us back to the world and not to God who is 180° away, at the level of substratum. Any unfulfilled desire will also lead to future births. In some temples, tulabaram is done for material benefits. But in Arunachala, the desire is for Egolessness. Having no desires and ego are the highest objectives of life.

Thus, those who have set their minds on the goal of liberation should start controlling their desires and attachments and strive to end them through enquiry and prayers. They should not allow their senses to run freely in the world but check them. They must also overcome all their faults, bad habits and negative emotions through enquiry and strive to make themselves pure and perfect. Only then, one will be able to make one’s mind subtle, fit for doing Atma Vichara or Self-Enquiry as taught by Bhagavan, which will take one to the discovery of the true Self within and uniting with it leading to the supreme goal of liberation. May Bhagavan help us at every step sothat we may attain the purpose of life in this very birth!

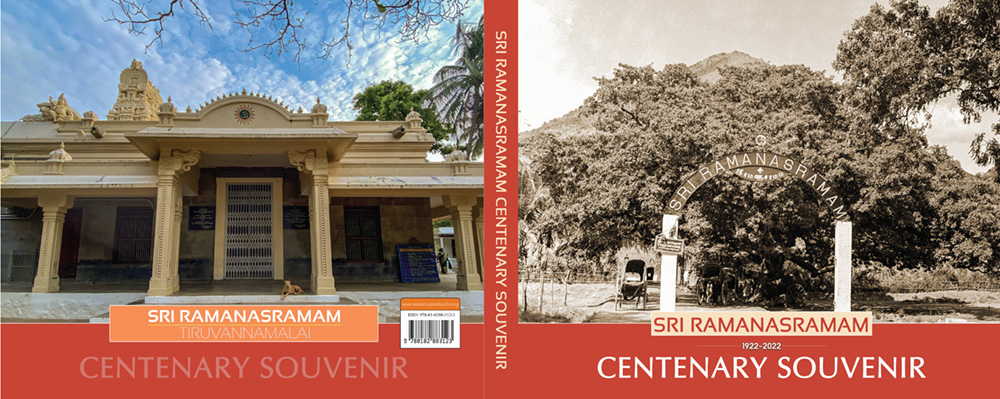

A visually stunning homage to Bhagavan Ramana and his Ashram unfolds within the pages of an enchanting coffee table book. With dimensions of 11 x 9 inches in landscape format, the book spans 280 pages and showcases over 400 photographs. Articles in English, Tamil, Hindi, Gujarati, Malayalam and Telugu contribute to the linguistic richness, reflecting the diverse audience.

Meticulously chronicling the evolution of Sri Ramanasramam, the book traces its journey from a modest single hut in 1922 to the expansive structure it became in 2023. Through a captivating blend of archival photographs, rare artifacts, and insightful narratives, readers are invited on a compelling journey through the transformative history of the ashram.

This exquisite volume stands as a tribute to the profound legacy shaped by the ashram over the past hundred years, encapsulating the spiritual essence of its evolution and preserving the enduring teachings of Sri Ramana Maharshi.

Priced at Rs.1000, the book offers a tangible connection to the remarkable history and teachings enshrined within the sacred grounds of Sri Ramanasramam.

THE MOUNTAIN PATH ARCHIVE

Self-Enquiry: Some Objections Answered

D.E. Harding

Every issue, we will select one article from the issue of Mountain Path that began publication in 1964 i.e., 60 years ago. This is an article that appeared in April 1964.

How is it that we need all this prodding, all these warnings and earnest invitations and promises of immense rewards, to persuade us to take a close look at ourselves? Why don't all intelligent and serious people make it their chief business in life to find out what they really are?

Surely, if such comparatively trivial questions as whether one is good-looking or not, popular or not, a 'success' or not, excite the keenest interest in us, the rather more important questions whether one is mortal or immortal, a body or spirit, created or Creator, should be that much more fascinating. Or so one would have supposed. To exist at all, somehow to have arrived on the scene — what astounding luck! — an intelligent something-or-other, and yet to remain uninterested in the nature of that something-or-other! It's incredible. Letting slip such an opportunity, foregoing (whether out of fear, laziness, or just negligence) the supreme privilege of discovering oneself, is more than unenterprising: it's a kind of madness, and none the less pitiful for being almost universal.

Thoughtful people, when challenged on this subject, are apt to excuse themselves by raising a number of objections to this inward search: they aren't at all sure it's a good thing. Of course (all agree) we need a working knowledge of our nature in order to make the best of ourselves and get on with others, but the probing can thrust too deep and go on too long. 'Know thyself' is all right up to a point, but shouldn't become an obsession, an end in itself, and certainly not our life's work: such introspection (they say) is likely to do more harm than good.And so: it's a selfish diversion of our energies from the service of others to preoccupation with ourselves; or it's a morbid introversion resulting in self-consciousness (in the bad sense) if not actually in mental illness; or it's time-consuming and unpractical, making us unfit for our jobs and even for family life; or it's depressing and dull, a dreadful bore, a dead end terminating in a mental blank; or it kills spontaneity and all natural, gay, out-going enjoyment; or it's a wonderful excuse for idleness and sponging; or it's coldly indifferent to art and to nature, to the beauty and wonder of the universe and the rich variety of the human scene, or it's a stupefying drug which reduces wordsto gibberish,stops thought, numbs the mind itself, exchanging our most highly-evolved human function for the nonhuman or subhuman Inane. More briefly, it's suspected that habitual looking within becomes selfish, unhealthy, futile, unnatural, idle, world-despising,retrogressive.In short, an escape. And the alternative?Apparently, it'sthat we should plunge right into the thick of things and find out what we are by living as fully as possible, becoming thoroughly involved in the turbulent and dangerous life stream instead of sitting down quietly and letting it flow by.

Of course, these doubts and criticisms aren't the whole story: underlying them lurk deeper fears and less conscious obstacles.All the same, there's something in them: they deserve to be taken seriously, and that is the purpose of this article. Its aim is to show that, in fact, the seeming weaknesses ofthis prolonged looking at oneself are itsstrength, and so far from being a retreat from reality it renounces that retreat. It's turning round and facing the central fact at last instead of running in all directions away from it. Indeed it's the true panacea, and ultimately the only way to full life, happiness, sanity, and even the effective service of others. Not that these statements are to be accepted on trust. The didactic tone of this article is merely for the sake of brevity: the fruits of true discovery are for tasting and not for dogmatising about. In this field, nothing's valid that we haven't tried out for ourselves.

First, then, take the accusation of selfishness. The typical Christian view is that we're not here to discover ourselves but to forget ourselves, concentrating on others and exchanging our natural self centredness for the other-centredness of loving service.

But how can we really do very much good to others till we know ourselves profoundly? How much of our so-called help is in fact working off our guilt-feelings on the world, trying to resolve our conscious conflicts regardless of the real need; and how often our short term help ends in long-term hindrance? It's notorious that material and even psychological aid, in solving one problem, is apt to create two more. Only the highest spiritual aid, given by one who really knows himself, and others through himself, can be guaranteed altogether beneficent and free from those unfortunate side-effects which go on and on so incalculably; and then the gift is probably a secret one, unexpressed and inexpressible. The truth is that helping oneself (which means finding oneself) is helping others, though the influence may be altogether subterranean. It goes without saying that we must be as kind as we can, but until we see clearly who is being kind we're working in the dark, with the hit-or-miss consequences that might be expected.

One of the troubles with this would-be forgetfulness of self in the service of others is that it's practically impossible: deliberate virtue rarely forgets to pat itself on the back a little. Goodness aimed at directly cannot avoid self-congratulation, and then its odour becomes unpleasant. But if, on the other hand, it's a mere by-product, arising naturally out of true knowledge of oneself, then it's quite indifferent to itself and any incidental merit or demerit, and so continues to smell sweet. Unfortunately, wrong effort to become a saint, or even a Sage, is a self-defeating (or rather, Self-defeating) enterprise ending in its opposite—an inflated ego. Whenever it's not a question of discovering the present facts but of somehow altering them, of achieving something in the future, then the ego is at work. The ego can't be defeated on its own ground. The only way to get rid of it is to turn from the time-ridden, ever changing outer scene where it thrives to the changeless Centre where it can never penetrate: in other words, the ego vanishes when one is oneself quite simply. Not only does the inward search promise to restrain or reduce our egotism: in the end, it's the only way of abolishing it. Truly speaking, there's nothing whatever to do—except clearly to realise that wonderful fact. All that's necessary is to examine the spot one occupies; here, always, lies Perfection. Here, the egoless, universal Self shines with utmost brilliance, alone. Only disinterested Self-enquiry succeeds, and then quite incidentally, in rectifying our attitude to others, because it alone unites us to them, demonstrating that in truth there are no others.

To call this enquiry selfish is to confuse the self or ego with our true Self. The genuine, liberating Self-enquiry is concerned with our essence, not our accidents or peculiarities. Unlike the ordinary man, the one who's engaged in this enquiry isn't at all interested in what marks him off from other men (his personal characteristics, history, destiny, merits, faults) but only in what he shares with all. Therefore his researches can never be for himself as an individual human: they're a universal enterprise on behalf of all creatures. No-one and nothing's left out. This way works, but the merely human way of laboriously overcoming self-centredness, by trying to centre oneself on other people (feeling for them, seeing things from their viewpoint, etc.) doesn't work in the end. The total and permanent cure is to find one's true Centre within, to become altogether present and Self-contained.

Can such an enquiry be morbid, nevertheless? What is mental illness, in the last resort, but alienation from others and therefore from oneself? It's the shame and misery of the part trying to be a whole (which it can never be) instead of the whole (which it always is). We are all insane, more or less, till we find by Self-enquiry our absolute identity with everyone else.

Self-enquiry is also suspected of being, if not actually unhealthy, at least impractical. Some colour is given to this objection by the fact (painfully evident to anyone who gets mixed up with religious movements) that 'spiritual' people are quite often cranks, misfits, or inclined to be neurotic. Actually, this isn't surprising. Contented (not to say self-satisfied) people, fairly 'normal' and well adjusted and good at being human, aren't driven to finding out what else they may be. It's those who need to find out who they are, the fortunately desperate ones, who are at all likely to take up the enterprise of Self-discovery. A sound instinct tells them where their cure lies, though few find it.

So it is that the wordling may appear (and often actually be) a far better man than the spiritually inclined. Looking within doesn't transform the personality overnight. All the same, it's a sigh of success in this supreme enterprise that it altogether 'normalises' a man, fitting him at last for life and correcting awkwardnesses and weaknesses and uglinesses. Now he's truly adjusted: he knows how to live, prosper and be happy. Paradoxically, it's by discovering that he isn't a man at all that he becomes a wholly satisfactory man. Naturally so: once he sees who he really is, his needs, and his demands on others, rapidly dwindle; his ability to concentrate on any chosen task is remarkable; his detachment provides the cool objectivity necessary for practical wisdom: for the first time he sees people as they are; he takes in everything and is not himself taken in. At the start, Self-enquiry may not be the best recipe for making friends and influencing people, but in the end it's the only way to be at home in the world. Nothing else is quite practical. Sages are immensely effectual men, not a lot of dreamy incompetents.

Ah (say those who don't know), but their life is so dull, so monotonous. How is it possible, attending for months and years on end to what is admittedly featureless, without any content whatever, mere clarity, to avoid a terrible boredom? Discovering our North Pole may be fine, but do we then have to live there in the icy darkness where nothing ever happens?

Now the extraordinary truth is that, contrary to all expectations, this seemingly bleak and dreary Centre of our being is in fact endlessly satisfying, sheer joy, absolutely fascinating: there's not a dull moment here. It's our periphery, the world where things happen, which bores and depresses. Why should the colourless, shapeless, unchanging, empty, nameless Source prove (in actual practice not theory) so astonishingly interesting, while all its products, in spite of their inexhaustible richness, prove a great weariness in the end? Well, this curious fact just has to be accepted — thankfully. It can hardly be a matter of serious complaint that everything lets us down till we find out who's being let down. If we would only allow them, all things push us Self-wards.

They do so naturally. In fact, the whole business of Self-discovery (though so rarely concluded) is our normal function, our natural development, failing which we remain stunted, if not perverse or freakish. Again, this is a surprising discovery. One would have imagined that any protracted inward gaze would have made a man rather less human, probably giving him a withdrawn look, an odd, self-occupied, and maybe forbidding manner.Actually, the reverse is true: only the Self-seeing man has the grace and charm of one who is perfectly free. To find the Source is to tap it. Take the case of the man who is morbidly self-conscious: there are two things he can do about it, the one a mere amelioration (if that) the other a true cure. The false cure for his shyness is to lose himself by moving out towards the world; the true cure is to find himself by moving in, till one day his self-consciousness becomes Self-consciousness, and therefore perfectly at ease everywhere. Nobody can, by any technique of self forgetting, regain the naturalness, the simple spontaneity of the small child or the animal; but by the opposite process of Self-recollection he can gain something like that blessed state, though at a much higher level. Then he will know, as if by superior instinct, what to do and how to do it; and, rather more often, what not to do. Short of this goal, we are all more or less awkward and artificial, more or less bogus.

Is this an easy way out—out of the hell of responsibility and involvement and constant danger into a safe and unstrenuous heaven? To look at the enquirer you might think so, but you couldn't be more mistaken. In a sense, admittedly, it's the easiest thing in the world to see what nobody else can see, namely what it's like to be oneself, what it's like here: the Light is blazingly obvious, the clarity transparently clear and unmistakable. But in another sense, alas, it's the most difficult thing in the world to see this Spot from this Spot: this mysterious Place one occupies, where one supposed there was some solid thing, a body or a brain, and where in fact is only the Seer Himself, is too wide open to inspection, too plain to catch our attention. All our arrows of attention point outwards; and they might be made of steel, so hard it is to bend them round to point in to the Centre, and still harder to prevent them springing back again immediately. Of all ambitions this is the most far-reaching, and no other adventure is anything like so daring or so difficult. This task, though clear and simple and natural, is also the one that requires more courage and persistence than most men have any idea of. The Sage hastaken on an immense job: alongside him, Napoleon is a weakling.And this work, which makes all other work seem like irresponsible pottering, is his perfect realisation that there's nothing whatever to do!

Is the result worth the trouble? Is there nothing of value out there, nothing worthy of our attention and love? Turning our backs on a universe so magnificent and so teeming, and on all the treasures of art and of thought, and above all on our fellow beings, is surely a huge loss. The Sage — so it's reported — isn't interested in these matters: the world consists of things he doesn't wish to know: for him, knowledge of particular things is only ignorance. Is his achievement, after all, so difficult and so rare only because it's fundamentally wrong to despise the world?

Once more, the boot's on the other foot. Oddly enough, it's the man who attends only to the outer scene, ignoring what lies at its Centre, who's more or less blind to that scene. For the world is a curious phenomenon that, like a faint star, can be clearly observed only when it isn't directly looked at. It's an object that will not fully reveal itself till we look in the opposite direction, catching sight of it in the mirror of the Self. Like the Gorgons, it won't bear straight inspection. This isn't a dogma, but a startling practical fact. For example, though the world is sometimes beautiful when directly viewed as quite real and self-supporting, it's always beautiful when indirectly viewed as a product or accident of the Self. When you see who's here you see what's there, as a sort of bonus. And this bonus is a delightful surprise: the universe is altogether transformed. Colours almost sing, so brilliant and glowing they are; shapes and planes and textures arrange themselves into charming compositions; nothing's repulsive or despicable or out of place. Every random patterning of objects — treetops and cloud banks, leaves and stones on the ground, human figures and cars and shop windows, stains and tattered posters on old walls, litter of all kinds — each is seen to be inevitable and perfect in its own unique way. And this is the very opposite of human imagination: it's divine realism, the clearing of that imaginative, wordy smoke-screen which increasingly hides the world from us as we grow older and more knowing.

Indeed the path of Self-enquiry is no escape route: it's the shortest way in, our highroad to the keenest enjoyment of the world. Yet, seemingly, it's incompatible with any other serious creative endeavour, whether artistic or intellectual or practical. If so, this is surely a considerable drawback.